When it comes to legal blogging, there seems to be no shortage of writing worth reading once one gets around to it.

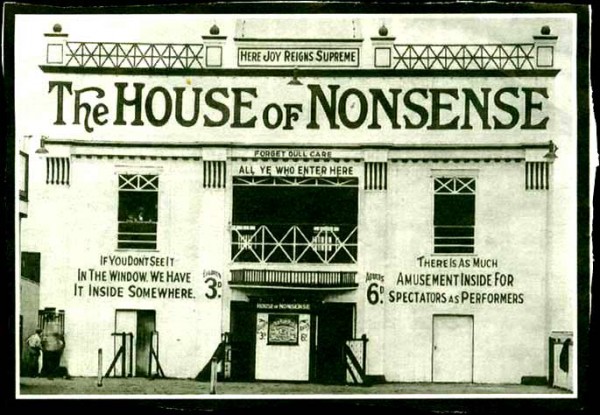

What's that? You have no round tuit? My friend, you are fortunate indeed, for never before in human history have round tuits been so readily available. If you need one, Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. has them in stock.

While you place your order, I'll share a few posts which are worth your attention.

Late last week, it was reported by the pop culture website RadarOnline.com that Chief Justice John Roberts was planning to resign suddenly, ostensibly due to health concerns. While this was surprising news to those in the legal community, it was particularly surprising for the Chief Justice himself, as he had no such retirement plans (or health concerns, presumably). It was an odd diversion from the more meaningful legal news of the week and David Lat and Kashmir Hill of the Above the Law blog set about attempting to unravel how such a strange rumor had begun.

David Lat worked to piece together a timeline of the various reports, retractions, and repostings and traced things back to an in-class exercise conducted by Georgetown Law Professor Peter Tague:

Like many a promising legal career, the Roberts resignation rumor traces its origins to a 1L class at Georgetown University Law Center….The whole episode made Dan Filler a bit nostalgic for kindler, gentler, less-connected times when law professors like Tague and himself could operate in a bubble:

Our criminal justice professor started our 9 am lecture with the news that roberts will be resigning tomorrow for health reasons — that he could not handle the administrative burdens of the job. He would not say how he knows — but halfway through our lecture on the credibility and reliability of informants he revealed that the Roberts rumor was made up to show how someone you ordinarily think is credible and reliable (ie a law professor) can disseminate inaccurate information.By then the horse was out of the barn — and running at a gallop:

[B]etween the hour when the class began and when he revealed that he made it up, plenty of students texted and IM’ed their friends and family…. [So] there’s a very good chance that the Roberts rumor that spread like wildfire on the internet was sparked by an eccentric law professor trying to make a point.We’ve reached out to the aforementioned eccentric law professor, by telephone and by email, but we haven’t heard back from him yet. If we do, we will update this post.

And that, dear readers, is what we do around here — we talk to multiple sources, including the sources most directly involved in a given story, in the course of our reporting. We exercise judgment in deciding what to report and when to report it. We do want to be first, but we also want to be right.

In Peter Tague's criminal law class yesterday, he shared the secret that Chief Justice John Roberts planned to resign. His apparent goal: to teach around the issue of the reliabilty of informants. But while this might have been an innocent (and probably useful) teaching strategy a decade ago, technology has transformed it into something much more exciting: the production of news! Because as you might expect, this information was twittered and emailed and blogged from the classroom to the Web. There it was dutifully reported by Radar Online. This led to a big scurry around D.C. to confirm or deny this rumor. ATL kept us up to date yesterday, and then deconstructed the whole event here.Kashmir Hill offered a good sampling of the discussion about the professor's stunt, his students' reactions, and the gullibility of more than a few online. Some chastised the professor for not considering the consequences of playing his trick in an age where his students are constantly wired into the world outside his classroom. One of Tague's former students noted that wired or no, the professor's previous classes were less naïve when this same lesson was taught in nearly the same way, year after year. Another former student also faulted the current crop of 1Ls:

At least nobody got hurt.

I took Tague’s crim class in spring 2002, and he pulled the same trick about Rehnquist. I can only assume he’s been doing the same thing every year for a long time, and each class since some time before 2002 has been filled with wired laptops. Yet this is the first time someone decided to publish the false rumor. So, it’s not just a doddering old fool not thinking that his false rumor would have consequences. It’s a prof who has trusted his students for years, and apparently with good reason until this year.A student who was in the class wrote that in spite of the unanticipated broadcasting, or perhaps because of it, Tague's lesson will be learned especially well by this year's class:

Personally, I think that Prof. Tague provided a fantastic lesson in precisely why it’s so important for attorneys to not only not believe everything they are told but also to act with discretion. I’m sure that he’s disappointed with the class as a whole, especially because he teaches professional responsibility courses, so I’m sure we will be receiving a talk from him about this.... [H]e certainly won’t have to repeat the lesson in the following years; all he has to do is tell this story.Hill and Lat collaborated on a "postscript" to their investigation of the Roberts rumors. Frankly, some appreciation for ATL as a credible news source is overdue; though many of us think of the blog for its provocative — even salacious — style, it demonstrates time and again that though it may do what it does with a sense of humor, it also takes journalism seriously and is run by grown-ups with a sense of what they're doing. It's a trustworthy source for legal news unlike, say, Radar Online or random Georgetown 1Ls. In this day and age, news travels faster but the line between news and gossip is thinner than ever.

The Roberts rumor wasn't the only bit of law-related nonsense this past week.

The legal profession has only just started to claw its way back from the image sinkhole caused by District of Columbia Administrative Law Judge Roy Pearson's $54 Million lost pants lawsuit. Now, Houston lawyer William Ogletree has decided to unpack his adjectives and threaten the City of Houston, Continental Airlines, and an airport concessionaire for the loss of a coat he left in a food court at the Houston Airport. (Via Walter Olson) The Smoking Gun reproduced Ogletree's magnum opus about his expensive black leather coat with plaid lining, which he affectionately referred to as "Rosebud" before it was lost to an uncaring world. I'm certain that Ogletree's law partner, Bill Abbott, was especially excited that Ogletree decided to use the firm's letterhead for his diatribe, thus associating Abbott's name with this embarrassment. The Consumerist blog highlighted the choicest bits:

Writes the charming fellow:Reached for comment, Roy Pearson said, "Holy crap! An $800 coat? With interest and penalties that's easily a $367 Billion claim. That airport had better settle immediately." After Patrick of the Popehat blog suggested that Ogletree should be more careful with his things in the future, his co-blogger, Ken, took him to task:

Each of the above-adressed entities are pointing their fingers at the other entities and all deny that they have the coat. Regardless of whether they have the coat, they were responsible for securing it and keeping it in a safe place for a reasonable time for the owner.And while the letter's author never says exactly how long he left his coat untended, he will never forget his experience at the food court:

I believe the name of the restaurant was Famiglia. However, I would volunteer to come to the airport and point out the restaurant and the person who waited on me. I remember her very well due to how badly she treated me.He closes his legal letter by saying they have 10 days to pay the $800 before he files suit.

This offer is only valid for 10 days from the date of this letter, after which this offer is permanently withdrawn. The amount will continue to increase according to the court costs, attorney's fees, investigation, expert witnesses and other damages available by law.

Only a cad would mock Mr. Ogletree because he can no longer remember where he has left his clothes and wanders about airports partially clad, snapping at fast-food-pizza clerks. This fate awaits us all, Patrick. One day you, too, will be irrational, easily upset, and forgetful, your once razor-sharp legal mind unable to frame a coherent theory of liability and confused about arrays of possible defendants, reduced to making impotent scattershot threats to municipalities and random corporations.I for one hope Ogletree prevails; as the father of a child who misplaces a minimum of fifteen garments per day at school and elsewhere, I could be a millionaire by year's end.

Time will lead you, too, to “lose your coat.” I hope then some mean-spirited blogger will show you more grace and pity than you have shown poor senile Mr. Ogletree.

It was acknowledged some time ago that nine appointees to the Obama Administration's Department of Justice had, while in private practice, represented detainees at the Guantanamo facility. More recently, the names of those nine were revealed by the right-leaning Fox News. This past week, a pressure group called "Keep America Safe" released a video which criticized the administration for appointing the attorneys and labeled the DOJ the "Department of Jihad". Ashby Jones noted that the video was swiftly condemned by many in the legal community on both right and left, and that the "Keep America Safe" group, which is affiliated with former Vice President Cheney's daughter, Liz, and conservative columnist William Kristol, had perhaps "gone a bit too far with their rhetoric". With tongue-in-cheek, Orin Kerr suggested that the group's message was not meant to be taken seriously; he ventured that Liz Cheney had been "invited to imagine how former Senator Joseph McCarthy would have used 30-second TV spots if here were alive today" and she offered this video in response.

The McCarthyite parallels weren't lost on others, either. David Luban wrote, "The slanders against government lawyers who represented detainees is an uncanny repetition of Senator Joseph McCarthy's hunt for Communists in government 60 years ago." He continued:

Interviewing Liz Cheney, Bill O'Reilly ran side-by-side photos of Deputy Solicitor General Neal Katyal and Salim Hamdan, Osama bin Laden's driver who Katyal successfully represented in the Supreme Court. (Neal Katyal, I should mention, is my Georgetown colleague, on leave to the SG's office.) Some readers might remember Steven Colbert's hilarious 2006 interview with Katyal soon after the Hamdan decision. Colbert began, "You defended a detainee at Gitmo in front of the Supreme Court -- for what reason? Why did you do it?" Neal replied: "A simple thing: he wanted a fair trial...." Colbert (cutting Katyal off): "Why do you hate our troops?" It brought gales of laughter from the audience. Watch the whole thing -- it's one of the few times that Colbert was actually upstaged by his guest.Eugene Fidell aptly characterized the attack on the DOJ appointees as "a nasty business which should offend every American":

First time farce, second time tragedy. Colbert's joke is Bill O'Reilly's reality -- the reality of a nauseating reprise of McCarthyism. No one is laughing now.

The effort to delegitimate the representation of detainees by treating as infiltrators those who have answered the call to public service in the current administration is beneath contempt. No such objection was raised when Royall was selected to be a brigadier general or senior civilian official. Nor did Adams’ representation of the Redcoats who perpetrated the Boston Massacre—probably the most loathed criminal defendants in Eighteenth Century North America—prevent him from succeeding George Washington.Political columnist Ben Smith noted that a number of other conservative lawyers had co-signed a blistering attack on the "Keep America Safe" group and its message. Ashby Jones reported, "19 lawyers had signed on to the letter, which, in broad strokes, defended those lawyers who represented terrorism suspects in recent years. Some of the bolder-faced names on the list include former Bush I [Solicitor General] and Whitewater prosecutor Kenneth Starr, former Bush II deputy Attorney General Larry Thompson, former Pentagon official Charles “Cully” Stimson (who resigned some three years ago over comments he made about the representation of terrorism suspects), and former Bush II White House lawyer Bradford Berenson."

....

What the detainees’ lawyers have done is in keeping with the highest tradition not just of the bar, but of our country. Don’t expect any of them to be recognized in the gallery at some future State of the Union address, but if some of them are willing to serve the nation, we should welcome them rather than vilify them, confuse them with their clients, or permit others to use them as a tool for undermining an administration that is simply trying to clean up the mess it inherited.

Eugene Volokh added his voice to the fray:

[T]he lawyers believed that their actions may (a) reduce the risk of factual error (continued detention of detainees who aren’t really guilty), (b) reduce the risk of legal and constitutional violations (deprivation of what the lawyer thinks are important due process norms), or (c) reduce the possible indirect harm that such erosion of due process norms can cause to others in the future. And they believed that, when a legal process is available — as the Supreme Court has held that it is — the legal system is benefited by having trained, qualified lawyers involved on both sides of the process, so that courts and other tribunals see an adversarial presentation with the best cases made for both sides. The lawyers’ actions were thus well within the longstanding and honorable American tradition of advocating for constitutional rights, even when one’s clients may well be very bad people.In an op-ed piece, former head of the DOJ's Office of Legal Counsel Walter Dellinger defended a colleague at O'Melveny & Myers, who was amongst those who represented the detainees on a pro bono basis. While Scott Greenfield agreed with Dellinger that the "Keep America Safe" video was a "shameful attack on the U.S. legal system", he suggested that the op-ed highlighted a double standard between establishment firms who "dabble" in defense work and those criminal defense lawyers who practice it day in and day out:

We are not welcome in their clubs. Our voices are not sought on issues of substance. When a new regime comes to power in our quadrennial peaceful coup, we are not invited to join their ranks. Indeed, when I once tried to offer my services during a fit of naive optimism to a new administration who claimed a sincere interest in justice, I was privately informed that, talking points aside, criminal defense lawyers were not wanted. We are the lepers of the legal system.Dellinger responded in comments to Greenfield's post that his "point is well taken, but badly misplaced with respect to O'Melveny & Myers." He described a number of notable (and lower-profile) defense matters handled by the firm. Whether those matters addressed the substance of Greenfield's argument or not remained in dispute; Greenfield wrote in reply:

In Dellinger's case, the epiphany came when his colleague at that radical law firm, O'Melveny & Myers, slummed by aiding the defense of Gitmo detainees. Honest work, but not what fills the firm's coffers. For Biglaw, defense is where they do pro bono, practice up on seldom used skills and feel as if they are doing something more useful than squabbling over how many options the new CEO will get with his golden parachute. It's the sort of thing they can point to when others complain that they're just vultures, sucking money out of large corporations to the detriment of mankind.

That they provide these types of services pro bono is a good thing, and Biglaw has done some great work on behalf of the poor and downtrodden, often in death penalty cases where the right to counsel had long since expired and solo lawyers couldn't possibly dedicate their energies without guaranteeing the starvation of their children. Many have benefited from these efforts, and that's great.

But they're just dabblers. This is something they do between mergers and acquisitions, not in lieu of it. You will never find anyone at Biglaw where black sneakers and hoping that no one notices they aren't really shoes. They wear suit jackets with working cuff buttons, leaving the bottom one unbuttoned so everyone will know. And they aren't prepared to be tainted permanently by the pro bono hours spent in the service of criminals.

We've been living like this forever, Walter. We do honest work. We are as much a part of the system as any prosecutor. Our contribution is vital, for without us there can be no system.

....

Maybe we have something to offer government, have the same interests and understanding of a nation run well, run safely, run with honor toward both the law and rights.

Clearly, OM&M, as well as other Biglaw firms, do a great deal of pro bono, but that was part of my point. It's not to say that your firm doesn't do some important work; it is to say that it's not quite what trench lawyers do, and for which we are routinely vilified.Brian Tannebaum understood Liz Cheney's attack on the DOJ Jihadis as well as anyone:

To be clear, most people believe the United States Constitution is meant to protect them, and not those who they think are guilty of a crime.

Take Elizabeth Cheney. She's on a campaign against current Department of Justice Lawyers who previously represented Gitmo detainees pro bono. She's part of the group behind this YouTube video.

The question is asked - if these are the lawyers defending these accused terrorists, who will, ready.......keep us safe?

It's been the mantra of the Right since September 11 - they, and not anyone else, are the ones who will keep us safe, and if we go against them, in any way, even mild disagreement, we will be less safe.

Nothing gets people more interested and excited than the notion that they may be unsafe. Scaring people, making them believe they are unsafe, you know, terrorism, is an easy way to get people's attention. It's done every day in Congress, state legislatures, local city counsels, courtrooms, schools, everywhere.

And it will never stop. It's like negative ads in political campaigns. We can criticize them all we want, but they work. Fear, works.

While he was supposed to be searching high and low in the Houston area for William Ogletree's expensive black leather coat with plaid lining, Mark Bennett was instead wasting valuable time down at the local courthouse, where a judge had declared the Texas death penalty procedure to be unconstitutional. The decision was widely misreported, though certainly through no fault of Bennett's. He posted the defense motion and the order signed by the judge, excerpted key sections of the transcript, and explained it all in considerable detail and with admirable clarity:

Beginning on page 26, Judge Fine introduces the notion that he’s the gatekeeper of the law, who has to decide “what our evolving standards of fairness and ordered liberty are.”To Bennett's continuing disappointment, this remarkable case was persistently misreported:

If—if they are such that society believes it to be okay to execute innocent people, whether that be one or a thousand so that a state, specifically the State of Texas, can have a death penalty so that those that might be deserving of the penalty of death can actually be put to death, whether or not that—that trade-off would meet our current standards of fairness and ordered liberty.This is the heart of Judge Fine’s rationale: that it’s his job (subject to appellate review) to decide what society’s standards are; that innocents have been will be executed; and that society is no longer, in light of increased knowledge of the danger that innocents will be convicted, willing to take that risk.

. . . .

With no other guidance from a higher court other than the guidance charging the trial courts with the duty of being gatekeepers, this is probably the most difficult decision I’ve had to make in my limited time on the Bench. But I am not prepared to say that our society, that our citizenry is willing to let innocent people die so that the State of Texas can have a death penalty.

The Houston Chronicle clings doggedly to the false proposition that Kevin Fine “declared the death penalty unconstitutional Thursday.”Blogger Bad Lawyer praised Judge Fine's political courage in rendering a decision which, he notes, is unlikely to survive appellate review:

....

The Chronicle may think it has some inside information suggesting that what the judge meant to do was to declare the death penalty unconstitutional, but court orders are word magic, and a judge doesn’t do any more or less than his orders say. It was clear from Thursday’s transcript and order... that the procedures, and not the penalty, were unconstitutional in the judge’s view.

The difference may not be apparent to the Chronicle’s lay readers, but it ought to be clear to a reporter with a law degree... and it’s a newspaper’s responsibility, abdicated in this case, to try to educate its readers rather than make up sensational news.

Can you believe it, a Texas Judge who doesn't want to be reelected!Jeff Gamso was also amazed at the judge's decision:

Wow, someone with judicial power in Texas who actually gives a damn whether innocent people get executed. I'm pinching myself.

God bless, Judge Fine!

What's interesting, though, is how he got there.In that post and in a follow-on post, Gamso contrasted the (temporary) setback the death penalty experienced in Texas this week with the continuing ups-and-downs capital punishment opponents have faced in Ohio.

He found somewhere a direction from the Supreme Court that, as a trial judge, he is to be a "gatekeeper."

All I can do, as this issue has been raised, is go by what guidance there is; and the only guidance that I have found is that provided by the United States Supreme Court that places a duty on trial courts to act as gatekeepers in interpreting the due process claim in light of evolving standards of fairness and ordered liberty.Really, it's one hell of a claim. And what follows from it is, perhaps even more impressive. The people, he concludes, don't think the death penalty is worth that cost.

Clearly I have been charged with that duty. So I am now charged with interpreting such evolving standards and I'm called upon to assess the current state of our society's standards of fairness and ordered liberty in light of what we as a society now know. That that is that we execute innocent people.

....

It's terrific sentiment. It's also, I suspect, terrifically naive.

The generation gaps amongst Baby Boom, Generation X, Generation Y, and Millenial-aged attorneys have been a frequent topic for discussion in the legal blogosphere of late. In a refreshing change of pace, Ernest Svenson had something very complimentary to say about the younger generation — their skills in managing multiple streams of data may make them better-adapted to the demands of digital lawyering in the near future:

Lawyers who don't search for things on Internet are the worst. They lack a fundamental skill that's needed to efficiently attack digital information. Naturally they're inept when it comes to handling electronic discovery. Some of them are committing serious malpractice. But, of course, they have no idea.Another frequent topic of discussion amongst lawyers online is social networking. For all the focus on the newest technologies and methods of meeting others online, however, it seems that a few of us may have forgotten how to do it offline. Discussing an article about a cab-sharing program in New York City, the Law Shucks bloggers noted that the odd couple pictured in the article — a hedge fund manager and an attorney who works with hedge funds — rode together all the way from the Upper East Side to Midtown Manhattan without managing to connect in the professional area they share. Exiting the cab, the hedge fund manager said to the hedge fund lawyer, "We should get together." Opportunity missed, said the Law Shucksers; they admonished the lawyer, "YOU SHOULD BE THE ONE SUGGESTING A GET-TOGETHER. Seriously, this is a golden opportunity. The guy is a potential client and he’s right in your wheelhouse!"

The next generation of lawyers will not have this problem, or at least it won't be a prevalent problem like it is today. The young turks coming out of law school today don't have a passive relationship to information. They attack digital information the way sharks attack wounded seals.

....

Law students today use the web like detectives. They know how to gather information (fine), but they instinctively know how to trace back the steps that other people use to find information. This mindset and the online research skills that come with it are dangerous. At least to some people.

For starters, these students will have a huge advantage when it comes to doing electronic discovery. They haven't even started practicing law and already they're leagues ahead of lawyers who've been in the business for years. They know how to gather digital information, and they have no resistance to adopting new ways of gathering it if that provides an instant advantage (e.g. no one is going to have to convince them of the value of concept searching). These lawyers will know how to zero in on key information quickly and inexpensively. So if I were a traditional lawyer (e.g. one with poor Internet skills or someone who has trouble with digital information), I'd be afraid of the next generation of lawyers.

The next generation will not graduate from law school and immediately surpass veteran lawyers. But they have a skill that's already in high demand, but short supply. Veteran lawyers can't quickly learn how to gather and process digital information. Most young lawyers will learn how to practice law fairly quickly, or at least much faster than the veteran lawyers will learn what they should be learning.

I highly recommend a couple of posts from Eugene Volokh. In the first, Volokh discusses NASA v. Nelson, in which the Supreme Court recently granted cert. In this case, the Ninth Circuit found that a fairly broad Constitutional right to data privacy existed; Volokh suspects that that finding isn't long for this world on appeal:

I see no basis in Whalen or in the Court’s other precedents for suggesting that there’s a constitutional right to information privacy that so constrains the government’s asking questions about people. The government doesn’t need the employee’s agreement to ask around about him, just as it doesn’t need a potential suspect’s agreement to ask around about him. There just isn’t a constitutional right not to have the government ask other people questions about you. So I’m glad the Court agreed to hear the case, and I predict that it will reverse. I’ll go further and say that I doubt there’ll be more than 2 votes to affirm the Ninth Circuit (at least on the informational privacy grounds), and quite possibly fewer.In another post, Volokh explains why we should be concerned about the free speech rights of the loathsome Fred Phelps and his congregation of hateful dimwits:

If the Phelpsians magically went to their reward tomorrow, public debate would suffer very little. But I think their speech needs to be protected, because allowing the restriction of such speech — especially using the “intentional infliction of emotional distress” tort — would lead to the restriction of much more valuable speech.Finally, struggling through a judicial opinion recently, Eric Turkewitz was dismayed by a pair of introductory sentences totaling 646 words; he did what anyone else would do — throw up his hands and declare a contest to find even worse judicial writing:

Now it’s true, as many have argued, that the Phelpsians’ speech is legally distinguishable from other speech that should be protected. A judge or jury could certainly hold other speech protected, even though some see it as outrageous and severely emotionally distressing, even if the verdict against the Phelpsians is upheld.

But to me the important question isn’t whether the other speech is legally distinguishable from the 1000-feet-from-the-funeral picketing — it’s whether the speech will indeed reliably end up being legally distinguished. I worry that it might not be, because judges and juries will be more likely to accept restrictions on other speech once the rationale of the anti-Phelpsian verdict is accepted.

Really, is such gobstopping exposition necessary? Have simple, declarative sentences been outlawed? Is clarity a crime?Will the Turkewitz Prize become for judicial writing what the Buler-Lytton Contest is for fiction? Here's hoping. "It was a dark and stormy night when the Plaintiff...."

I challenge anyone to find a sentence in another judicial opinion of such length.

....

So let me politely suggest that our appellate judiciary do a few things:

1. Read the opinions of Justices Scalia, Posner, or Kozinski. Just for style. Ask yourselves this question: Would any of those jurists compose anything resembling the mind-numbing legalese I've re-printed below?

2. Contact legal writing guru Bryan Garner, who has given a gazillion seminars on writing to lawyers and judges;

3. Take the writing manual that you are working from and dump it. Whatever comes out the other end of the recycling process will be of better use.

Header pictures used in this post were obtained from (top to bottom) Carbolic Smoke Ball Co., haute-courier.nl, Wikipedia (Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn), and Paris Odds n Ends Thrift Store.

No comments:

Post a Comment