When it comes to legal blogging, there seems to be no shortage of writing worth reading once one gets around to it.

What's that? You have no round tuit? My friend, you are fortunate indeed, for never before in human history have round tuits been so readily available. If you need one, Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. has them in stock.

While you place your order, I'll share a few posts which are worth your attention.

Has the legal blogosphere become a "Happysphere" where criticism is considered unmannered and applause is expected for any contribution? In the years since I first posted here, the character of the space has certainly changed — many times, depending on how nuanced your analysis might be. In many ways, I think it's fair to say that overall, the Happysphere ethos dominates.

With few exceptions, you can choose nearly any marketing-centric blog and find equal measures of warmed-over "next big thing" cheerleading from last week's social media conference, effusive praise for other marketers, and quoting of other marketers' effusive praise for oneself. Again with few exceptions, one is safe in dismissing these blogs outright — these add nothing meaningful or consequential to our discussion. Those few exceptional marketing-concerned blogs tend to be engaged in other areas of the legal blogosphere, so you needn't be concerned about overlooking them if you steer a wide path around the marketeers.

When I began reading blogs and posting to my own, the legal blogosphere seemed equally divided between practitioners — generally, solo practitioners or those in very small firms — and academics. While there's never been a tremendous amount of interaction between those two groups, there was always a give-and-take within them. Practitioner-bloggers highlighted, discussed, and criticized other practitioners' posts in posts of their own and in comments around the legal blogosphere; academics did the same for their side (although they tended to be so polite about it that we non-academics often couldn't tell if they were disagreeing).

The influx of add-nothing marketers and their incessant commercialization of every facet of the legal blogosphere marked — for me at least — the end of the era in which I joined. I'll admit to a certain suspicion of newcomers these days; the vast majority of them are obviously driven by the marketing pitches they've heard and the others... well, I just assume that their marketers are a bit more subtle unless and until those bloggers demonstrate that their voices are genuine and the contents of their blogs are substantive and informed. Most new blogs I read manage one of these, or even a couple, but not all of them — or at least not for very long — and fall off the reading list within a few months if their proprietors haven't already given-up on blogging in the meantime.

Whereas earlier entrants were driven by their desire to communicate their own ideas and experiences and engage with others, most newer entrants are driven by other concerns. The marketeers weren't here in the beginning; the legal blogs built to maximize SEO values and composed of scraped content or content written by non-lawyers weren't here in the beginning; the BigLaw blogs, which ably summarize current legal issues but usually don't offer much perspective and don't attempt to engage with other bloggers, weren't here in the beginning. They're all here now, and their sheer numbers have diluted the legal blogosphere to the point that, on the whole, it's no longer characterized by the substance and engagement it once was. It's a Happysphere because a significant portion of it is comprised of blogs without substance, disengaged bloggers, and happy marketeers. Criticism is absent because it gains these players nothing.

I'll admit to more than a little frustration of late with the state of things. Is this a thing worth continuing? Into my sixth year of doing this, one would think that I have some answers, but I don't. I honestly don't. Part of my frustration stems from my somewhat vested interest in a healthy legal blogosphere. I've spent a number of years here trying to do what I could to see that new readers could find bloggers who had something meaningful to say, a clear voice with which to say it, and enough backbone to criticize and be criticized in return. There are still many, many bloggers who fit that bill, but it seems that neither they nor I can hope to hold back the tide. With a vested interest comes a loss of perspective, I fear.

Thus, I've found over the past year or two that Twitter is a wonderful respite. Though I've been on there for awhile now, I have no vested interest in it. It's a Happysphere and doesn't pretend (much) to be otherwise. Venkat Balasubramani put it well recently when he characterized Twitter as a "Cult of Positivity", distinguishing it somewhat from the blogosphere:

Twitter is a big place, and I can't speak for much of Twitter, but my impression is that the mainstream Twitter user is overwhelmingly positive. Positivity certainly reigns supreme in the corner of the Twittersphere that I frequent, and my impression is that there are other pockets of it that are overwhelmingly positive as well. Twitter is all about highlighting positive things and people.... while there are a few people who call it like they see it, most legal birds are effusive in their praise and quick to withhold criticism. And this extends to points of view taken, articles passed around, etc. It's almost as if it's socially unacceptable to say that something sucks.I think that's a fair criticism. In these "Round Tuit" posts, I've often highlighted posts which I believe are worth reading but don't necessarily agree with or posts which shed some light on an important issue but miss the point overall. The blogging medium allows me to do this but explain my disagreement or add some context. I can't do that on Twitter, no matter how many 140-characters messages I string together; Twitter is simply not suited to any sort of meaningful discussion. The net result is that discussions I see in my Twitter stream are by-and-large pleasant but superficial ones. Occasionally there's a more engaged discussion and just as occasionally a heated argument. It's cocktail party chatter, essentially, and as it is at a party, people mix and try to keep things light. Well, at least that's how I remember cocktail parties; I've not had a drink in fifteen years, so perhaps things have changed. For all I know, cocktail parties these days are marked by deep discussions and high drama.

....

I do note the negative effects of overwhelming positivity: bad content gets passed around freely and praised. Bad ideas too. Bad conferences. Bad people. Bad media. Blogs are a much much better filter of stuff for me (granted you can say more when you are not limited to 140 characters). On Twitter, I'm routinely disappointed with what someone (or many people) often describe as a "great article!"

Scott Greenfield touched-on a key problem with Twitter — separating the relevant information from the irrelevant, even amongst those people whose views we respect in the real (or virtual) world outside the Twittersphere:

Some people retwit anything written within a genre or topic in which they have a significant interest, but do so without editorial comment. I don't know what that means to anyone else, but it says to me that you endorse it.It's a frustration, albeit an easily-remedied one, when someone proves to be an unreliable source of information on Twitter. I think it's fair to interpret retweets as endorsements, though I've come to learn which of the folks I follow routinely retweet worthwhile posts which offer a perspective different from their own. There are many people whose blogs I trust who I find unbearable in 140 characters or fewer. There are others whose posts and tweets I follow closely but for markedly different reasons. There are even a few who will always have a place in my Twitterstream but never one in my RSS reader.

....

The problem is that twitter just isn't a viable medium for expressing critical thought. It allows for the snide remark, but not the reason behind it. It would be great to make enemies, but poor to challenge ideas (or the lack thereof). Which means that it's a fine medium for a pat on the back, a cute statement, some fun chit chat.

But all of this is what's led twitter down the positivity path to pointlessness. Does it not get boring, really quickly, to engage in some half-witty repartee with people you don't know about things that don't matter? Why do we engage in pleasantries with a disembodied name and avatar when we could be speaking to actual people whom we know to have some value to our lives? It's not to call these unknown twitteratti worthless, but rather to say that their relevance is (a) as yet undetermined, or (b) too superficial to be worth the time.

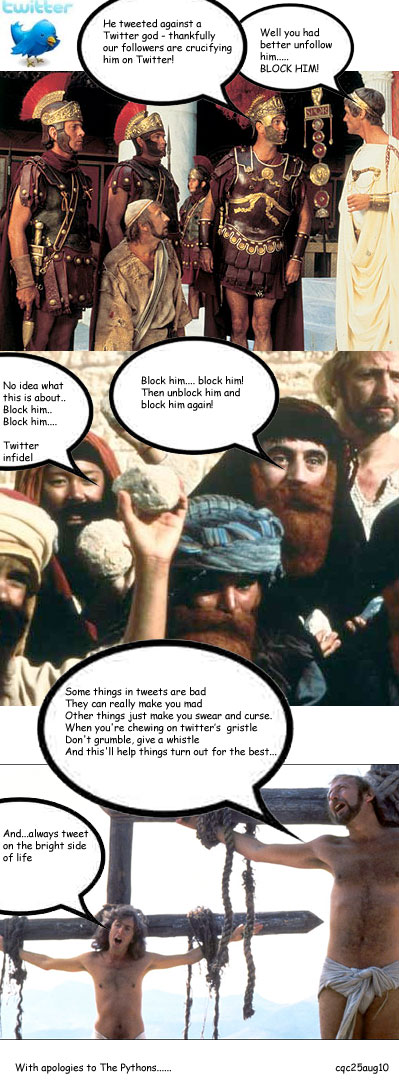

To the extent that I've followed people who, as Greenfield writes, "retwit anything written within a genre or topic in which they have a significant interest", I've unfollowed them just as quickly. There's no point in following someone on Twitter who recommends everything they've read any more than it's worth your time to listen to someone who recommends every movie he's seen, just to let you know that he watches a lot of movies. The quiet unfollow is your friend. Still there's something eminently satisfying about the piling-on one sees from time-to-time when someone transgresses the unwritten laws of Twitter. It's said that a picture is worth a thousand words, but that's severely devaluing this masterpiece from Charon QC on that topic:

I've been selective about which social media I've adopted. I skipped (with a couple of exceptions) the listservs, newsgroups, and discussion groups in favor of blogging. I skipped MySpace and Facebook in favor of LinkedIn. I'm on Twitter but I'll never be the mayor of anything on Foursquare and you won't find me on Tumblr, Flickr, or any other site developed by hipsters who can't find the letter "e" on their keyboards. All in all, if there's a common thread amongst the social spaces I've joined, it's that blogging, Twitter, and LinkedIn have connected me with and kept me connected to the sort of people I would choose as friends offline. If I had any friends offline, that is. As my sister once pointed-out, I no longer need to clarify that someone is an "online" friend because those are the sort I favor and for the most part, the only ones I have.

Notwithstanding, I appreciate that those whom I count as friends are a distinct group from the many others I interact with online. In this, I think there's still some meaning to the concept of friendship in the online world; whether it's materially different than friendship in the offline one is worth discussing. Mark Bennett did so recently:

Before I euthanized my account there, I had hundreds of “friends” on Facebook. Most of them I knew only slightly; some of them I didn’t even really like. Precious few of them were genuine friends.Mike Cernovich suggested that asking who one's friends are is asking precisely the wrong question; instead, he advised us to ask "To whom am I a friend?" He wrote:

Someone (I wish I could find a link to give proper credit) coined the term “frends” to represent those online acquaintances—similar to friends, but not quite—a variance that makes all the difference in the world.

A true friend is one who, when he finds out you are in trouble, will drop what he is doing and do what he can to help. Want to know how many genuine friends you have? Get charged with a serious crime.

....

Facebook devalues friendship by calling something that when it isn’t truly: six hundred frends, and if you’re extraordinarily lucky two or three friends.

Who are your true friends? (A benediction: May you never find out!)

More importantly (and more in your control), are you a true friend?

To be a great friend puts the action where it should be - on ourselves. When's the last time you go out of bed at 3 in the morning to bail a friend out of jail? Loan a friend a grand? Or to jump start a car? Or to listen to someone bitch about stupid shit?Scott Greenfield happily noted that this friendship discussion reminded him of the good old days in the legal blogosphere, when someone would write something on a side topic "and somebody else quibbles for kicks"; "I want in," he wrote:

Friendship requires elevating the other person - your friends. When I have money, my friends have money. It's really that simple. Friendship is a sort of voluntary socialism. Of course there will always be the occasional mooch, but one can get an STD from having sex. Does this mean you stop having sex - or that you start being careful? So, too, it is with friends.

Who are you a friend to? If you wouldn't come pick me up at 3 a.m. when my car broke down, you're not my friend. Why waste time and energy pretending we're friends? We're not, and that's cool, and friendship is so great that you should devote your time to someone who is actually a friend.

....

When you start thinking about what you can do for other people, something contradictory happens: People start thinking about what they can do for you.

....

We are not what we say or think, but are what we do. We become what we do. If we do good things for people, even if we begin as sons of bitches, we change.

It will likely come as surprise to some readers, particularly those without a sense of humor or a great deal of life experience, that I'm a pretty good friend to others. Despite my playing the curmudgeon and my refusal to coddle the needy and whiny, I'm usually there for people in need, real friends and even casual acquaintances. Even those I only know from the internet. It's my nature to try to help, regardless of whether the problem is self-induced foolishness or bad luck. I'm the guy you want standing behind you in a fight. There are a good many of you out there who I've help over the years, and you know who you are.I suspect that Bennett, Cernovich, and Greenfield are all right to some degree. Virtual friends and followers may not be real friends in need; be considerate of others without worrying about reciprocity and others' friendship will naturally follow; and when you stop to take score, the numbers will likely not be in your favor, so it's probably best not to keep score. All this noted, I'm happy to say that my sister's comment is true — there's not much difference in my mind between my online friends and my offline friends. I'm also happy to say that of the hundred or so people I'm linked with on LinkedIn, of the few hundred who follow me on Twitter, and of the few hundred more who read my blog regularly, more than a few I can count as friends by any measure. I'm happiest of all that I can count at least a couple in this section of Round Tuit alone (and I'd be honored if they'd say the same about me). Hell, I'm a one-man Happysphere.

And in return, not much. For some, it's a matter of narcissism, where you "deserved" help and I did nothing more than gave you what the world owed you. For others, it's selfishness, that you are happy to take but disinclined to give. For a few, it's low self-esteem, where you resented me for helping you (hey, you asked) and became angry with me for your sense of "debt" on your shoulder. Sometimes it's a combination of motives and issues, but the net result is the same. Help someone and make an enemy for it. Or at least not a friend.

By my highly unscientific calculations, the friend to friend ration is 10:1, with 90% of those you befriend either failing to return the friendship or actively disliking you for having done them a solid. If you're looking for a return on investment, being a good friend sucks. If you help others because that's just the way you roll, then it doesn't matter. You help others without any expectation of friendship in return, and your expectations are met.

But Mark's post raises a more ominous specter, that those who look for friendship online, and who harbor the bizarre belief... that their Facebook friends or Twitter followers are their real, true, honest-to-god buddies, are in for a rude awakening. A friend on Twitter is a frendship quitter.

When time comes to post bail, see how many of your followers show up with cash in hand.

It's long been a truism that a person with two or three good friends is rich indeed. If anything, the internet may not have enhanced our wealth, but taken from it. With the time spent online worrying about how to spread our wit about at 140 characters at a time, chances are good that people have neglected their real-life friends for their virtual "frends" and end up with neither.

Oh, and Mike? Put me on speed-dial. If your car breaks down at three in the morning, I'll be there with bells on.

While I'm on the subject of the "good old days" of legal blogging, I'll highlight a great series of posts illustrating one of the strengths of the medium which used to be commonplace and is no longer — the knowledgeable practitioner ably dissecting and debunking something which was swallowed whole by the established media.

In this instance, the part of the knowledgeable practitioner was played by knowledgeable practitioner Mark Bennett; the part of "something" was played by a recently-published research paper which concluded that the results gained by public defenders were essentially the same as those secured by private defense counsel. A fine conclusion, certainly; would that it was supported by the researchers' own data, wrote Bennett:

As he made his way through the research paper, Bennett added a few more concerns about the authors' methodology and conclusions, noting that of the ten results identified, seven favored private defense counsel:Black defendants who retain a private attorney are almost two times more likely to have the primary charge reduced than black defendants who are represented by a public defender.That’s a quote, according to Miller-McCune, from a research paper by Richard D. Hartley.

....

Hartley’s conclusion [is] that “there is little difference in the quality of legal defense provided to defendants by private attorneys and public defenders.” Does “little difference” mean the same to Dr. Hartley as “almost two times more likely”? Or do black defendants just not count?

I won’t call it sloppy without reading it, but the methodology of the study is suspect—if you don’t know whether hired lawyers beat more cases outright than PDs, how can you possibly reach such a conclusion?

[T]he numbers are statistically insignificant—that is, there is calculated a more-than-5% chance that they are due to chance—but all point in the same direction, which suggests that they are not due to chance.Bennett continued:

Hartley and his colleagues claim that:This study suggests that there is little difference in the “quality” of legal defense provided by private attorneys and public defenders. Public defenders are as effective as private attorneys in Cook County.Unless that’s the result one is looking for, the study—as Hartley and his colleagues present it—suggests no such thing. Don’t believe me? Ask a black defendant. Or an employed defendant. Or a male defendant. Or an unemployed defendant. Or a defendant who pled guilty. Or one who’s out on bail. Or one who’s detained.

[I]n Hartley’s data (Cook County 1993) defendants who were convicted after trial were 3.48 times as likely to be incarcerated, and received sentences 46.87 months longer, with hired lawyers as with public defenders.In his final post, Bennett admitted that part of his pique about the study was due to the authors' characterization of public defenders' motivations and ethics:

One way to account for this is as Hartley and his colleagues do: “These findings reveal that the so called jury trial penalty might only be applicable for defendants who retain a private attorney.”

Another way to account for it is this: these findings reveal that, because they have more confidence in their lawyers, facing severe sentences, defendants with hired counsel might be more likely to go to trial than defendants with public defenders.

Or this: these findings reveal that defendants with hired lawyers might be likely to try less-defensible cases, thereby irritating judges and inviting a trial tax.

Or even this: these findings reveal that people facing serious charges and maintaining their innocence, who if they lose will be more severely punished, might be more likely to hire lawyers than others are.

For Hartley’s statistics to mean anything at all about the relative merits of public and private counsel, we would have to know how many cases each type of lawyer got dismissed or acquitted or, at a bare minimum, how many cases in Cook County were dismissed or acquitted in 1993....

Aside from their sloppy writing and questionable conclusions, the collaborators wrote a couple of things that really ticked me off.With Mark Bennett as the knowledgeable practitioner and the Hartley study as the something debunked in this drama, who played the established media outlet which should have asked the tough questions but didn't? Scott Greenfield filled-in that blank for us:

First, they consistently wrote about what happens to human beings in a criminal courthouse as “case processing,” as in:Public defenders, like prosecutors and judges, want to ensure the smooth and efficient processing of cases.That’s downright libelous to all of the ethical and conscientious public defenders who, rather than wanting to ensure the smooth and efficient processing of cases, want to make it as difficult as possible for the state to put their clients into boxes. We’re not making Soylent Green, we’re fighting for souls. Some prosecutors and judges may think of what they do as case processing, but nobody who shares that view is welcome at the counsel table with me.

[T]he same study is presented to lawyers via the American Bar Association Journal, the house organ of that most august of legal institutions. The headline reads, Public Defenders Often are Just as Effective as Private Counsel, Study Says. The accompanying story, just a blurb really, offers some spurious disconnected results.Brian Tannebaum began his career as a public defender before making the transition to private defense work. Though he didn't weigh-in on the Hartley study or Bennett's and Greenfield's comments on it, he wrote about the "core" of a criminal defense lawyer, regardless whether a public defender or private counsel:

....

The internet is a veritable cornucopia of information. Some of it is just horrendously bad, and often dangerously so. Bennett's discussion of this study added value, incisive analysis of a study that was doomed ab inito to serve any viable purpose by its inability to take into account the myriad factors that exist in the real world, as well as the author's ignorance of the system.

Juxtapose the ABA Journal's treatment, which serves to make its reader more ignorant by having fed them snippets of the study without any critical thought whatsoever. Their readers walk away with misinformation from which to guide their decisions, courtesy of the ABA Journal. This subtracts value from the internet by feeding people something that can only cause harm by promoting ill-founded notions.

....

Instead, a silly study with some very dangerous conclusions made headlines at the ABA Journal, and lawyers and defendants who read it will be worse for it. After all, if the ABA Journal, the house organ of the august American Bar Association, says so, it must be true.

[I]f I ever get to the point where I don't have to work anymore, I may consider going back to that life of being a public defender. I loved it, I just became bored and wanted to handle other types of criminal cases, do federal work, and have the luxury not to have 150 cases.Responding at length to an anonymous commenter, Tannebaum summed-up the meaning of criminal defense as succinctly as I've heard it: "Rationalizations? I have none. I do what I do because I believe in the Constitution, I believe in this country, and I believe that anyone charged with a crime deserves a good defense...."

But lately I walk into a courtroom. I stand in the well and I look at that same jury box, with (some of) those same inmates.

I think they look at me differently these days. maybe its the suit, maybe it's the one file in my hands, maybe it's the way the judge greets me as opposed to "go talk to your client," or "have you made these plea offers yet?"

I think they know I'm not a public defender, and think (wrongfully) that my entrance into their case would be their ticket out of the system. I look at their tired eyes, their agitated faces, and I wonder if they think I'm some big shot private lawyer who has no use for them, or if they wish they could gather up some money to have a lawyer like me. A private lawyer. A "real" lawyer as they mistakenly think.

....

We criminal defense lawyers know too well about the poor client we were appointed to represent who gets convicted and sent to prison that says "thank you for fighting for me," and the private client who paid a fee, had his case dismissed, and wonders out loud why they ever needed a lawyer.

If there's a God, I thank Him for guys like that.

This past week, Mike Masnick and his colleagues at the Techdirt blog had a scare. No, not "scare"; what's the word I'm looking for? Oh, yes... "laugh". This particular laugh came at the expense of an English solicitor who'd be better-off reading Techdirt rather than attempting to shut it down. Masnick noted that while the site doesn't make a practice of outing everyone who sends them a legal threat, he was willing to do so in this instance:

The threats are quite incredible, demanding that we shut down the entire site of Techdirt, due to a comment (or, potentially, comments) that the client did not like.At the Popehat blog, Ken termed the SPEECH Act "a bulwark against buffoonish Brits":

....

Most importantly, this threat is coming from the UK, and the lawyers insist that they will take it to court in the UK. This makes it rather timely and newsworthy for an entirely different reason. Just a few weeks ago we wrote about the new SPEECH Act that was passed into law to protect against libel tourism. As the Congressional record shows, the law was specifically designed to protect US businesses from libel judgments that violate Section 230 -- and the bill's backers explicitly call out libel judgments made in the UK. In other words, the SPEECH Act explicitly protects us from exactly the sort of threat that these lawyers and their client are making against us:The purpose of this provision is to ensure that libel tourists do not attempt to chill speech by suing a third-party interactive computer service, rather than the actual author of the offending statement.Separate from the Section 230 defenses, we are also protected due to a lack of personal jurisdiction, which, again, is supported by the recently passed SPEECH Act. It is entirely possible that the lawyers were unaware of the SPEECH Act, but it does seem like a law firm making legal threats in a foreign country should be expected to have researched the legal barriers to making such a claim before using billable hours to make threats they cannot back up.

In such circumstances, the service provider would likely take down the allegedly offending material rather than face a lawsuit. Providing immunity removes this unhealthy incentive to take down material under improper pressure.

....

Thanks in part to the new law, we have no obligation to respond to Mr. Morris, his friend or the lawyers at Addlestone Keane, who (one would hope) will better advise their clients not to pursue such fruitless legal threats in the future. Should Mr. Morris and his solicitors decide that they wish to proceed with such a pointless and wasteful lawsuit against us, which will only serve to cost Mr. Morris significant legal sums with no hope of recovery, we will continue to report on it, safe in the knowledge that it has no bearing on us. The only potential issue I could foresee would be that any UK judgment against us could prevent me from traveling to the UK in the future, which would be unfortunate, as I have quite enjoyed past visits to the UK. But perhaps such ridiculous outcomes will help the UK realize that it's really about time to update its incredibly outdated libel laws and begin respecting free speech rights.

[T]he Speech Act is an effective shield to prevent libel tourists from enforcing shitty foreign defamation laws against Americans. Hence countries that have terrible, censorious libel laws that encourage libel tourism, or have ambitions to police the internet by allowing foreign suits for things written on web sites hosted in the United States, will be thwarted — they’ll be left with a useless foreign judgment unenforceable against people in the United States.As my friends (and a few "frends") know, I'm a sucker for a complicated trademark story, and the longer and more convoluted the better. Thus it was that I found myself engrossed this week by Ryan Giles' "Convoluted and Complicated History of the TROPICANA Hotel/Casino Trademark". He wrote:

....

Thanks to the SPEECH Act, Addlestone’s foolish threats are impotent. Even if he gets some pseudo-court in England to issue an injunction and damages award under the United Kingdom’s loathsome defamation law, he’ll never enforce it here. It will be, like Addlestone’s diploma, an expensive but ultimately pointless scrap of paper. A United States court will never enforce an injunction taking down an entire web site on the theory that a post was defamatory. A United States court will never enforce a defamation judgment premised on a statement by a commenter; that would violate Section 230.

A cautious lawyer, before sending such a strident threat, might have checked first to see if there had been any recent developments in the law governing perfection of foreign judgments, particularly because prior versions of the SPEECH Act have been floating about, well publicized, for some time.

What started out as a simple declaratory judgment action by the new owners of the Tropicana Las Vegas regarding their long-time right to use the name Tropicana in connection with the hotel/casino located at the intersection of Las Vegas Blvd. and Tropicana Avenue has recently expanded into a fight over actual ownership of the TROPICANA trademark. While the Las Vegas Sun published an succinct article last week... regarding the lawsuit filed in Delaware Bankruptcy Court by a group of companies lead by Carl Icahn's Tropicana Entertainment Inc. ... the actual factual circumstances giving rise to the instant dispute regarding ownership of the TROPICANA mark are interesting enough (and so amazingly convoluted) that I felt a more detailed discussion of the facts underlying the ownership dispute was merited – if anything to provide another illustration of how trademark rights are handled in the course of multiple large scale corporate transactions (including bankruptcy proceedings) and how certain things can (and indeed do) fall through the cracks.Interesting, convoluted, and with multiple diagrams! If you make it through the whole thing, you'll get comped at the breakfast buffet and receive a free spin on the money wheel.

Over the next few weeks, hopeful (if apprehensive) 1Ls will enter the hallowed halls of law schools across the country and begin accumulating crippling student debts which will haunt them for decades after they graduate and manage to find a job somewhere other than in legal practice. Rather than advising them to cut their losses and leave law school now, as most of us would have, Elie Mystal offered those 1Ls a bit of constructive criticism:

[T]he time for being a passive participant in your own education is at an end. If you think that you can be ready to function as a good attorney by going to class, preparing for panel, and writing your way on to law review, you’ve got your head up your ass. You said you wanted to go to law school, you said you wanted to learn — now you have to go out and make it happen for yourself. Nobody is going to give you a useful education (even though you’re paying through the nose for it); you have to go out and take it.Yes, good luck to you all. On The Paper Chase, Professor Kingsfield famously belittled series protagonist James Hart, telling him, "Mister Hart, here is a dime. Take it, call your mother, and tell her there is serious doubt about you ever becoming a lawyer." Things are not as bad for today's 1Ls, of course. Unlike students of Mr. Hart's era, today's law students have mobile phones and free internet calling at their disposal, so they needn't wait for an overbearing professor to spot them change for their call.

Paying more attention in Legal Research and Writing this fall than you do in something “law sounding” like Torts is a good start. When you have the opportunity, you should be taking every clinical program your school has to offer. But really, it’s about attitude and focus. Opportunities will present themselves to learn something about the actual practice of the law. If you go in with your head on a swivel looking for those opportunities, you’ll know to seize them when they present themselves. You’ll develop relationships with adjunct professors who actually have their own practices. If you spend three years looking to force your way into some practical knowledge, maybe you won’t be “worthless” when you graduate.

Or, you can sit back, dutifully learn whatever pet theories your professors have on contract law, and feel all warm and self-satisfied when you get an “A.” It’ll be fun. And three years later, the only thing you’ll be qualified to do is beg a private firm to pay you a salary while they actually teach you how to become a lawyer. Good luck with that.

Header pictures used in this post were obtained from (top to bottom) Carbolic Smoke Ball Co., explodingdog.com, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and Paris Odds n Ends Thrift Store.

No comments:

Post a Comment