When it comes to legal blogging, there seems to be no shortage of writing worth reading once one gets around to it.

What's that? You have no round tuit? My friend, you are fortunate indeed, for never before in human history have round tuits been so readily available. If you need one, Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. has them in stock.

While you place your order, I'll share a few posts which are worth your attention.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair....The Federal government tangled with the States of Arizona and Virginia in a pair of matters this past week and it was a best-of-times/worst-of-times outcome for us; it depended on one's philosophical and political bent to say which of these (preliminary) decisions represented wisdom, belief, Light, and hope and which was foolishness, incredulity, Darkness, and despair.

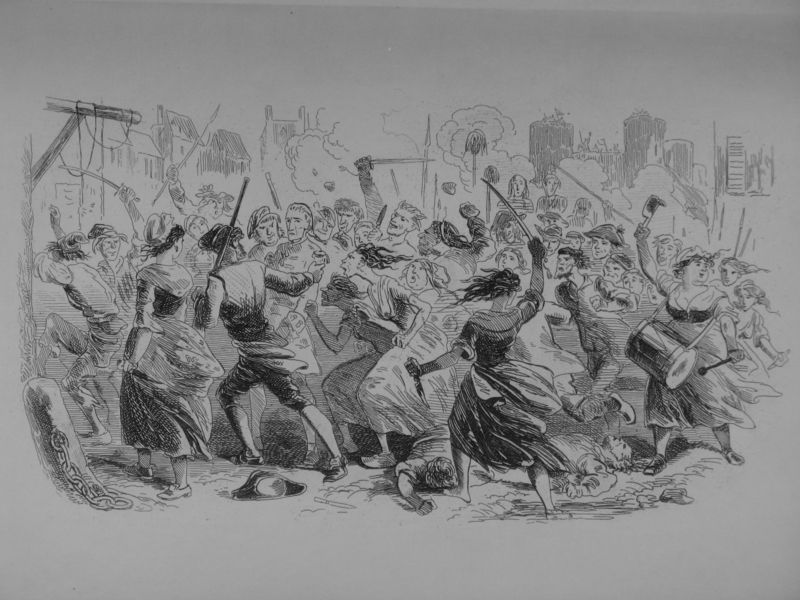

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

For those coming late to the party, the citizens of the State of Arizona, frustrated by what they perceive as a Federal inability or unwillingness to enforce immigration laws, determined that their law enforcement authorities should take a more active role in immigration enforcement within the state. Reasonable minds can differ as to whether that's a wise or appropriate response to the problem. Even amongst those who would ordinarily favor greater enforcement of immigration rules (or even more stringent rules), there's been much concern about what else the Arizona law would do, its methods, and the constitutionality of the scheme under our Federal system.

Regardless its advisability or legality, one might reasonably say that the Arizona measure (known as SB1070) brought to a boil the long-simmering national debate about illegal immigration and has focused legal attention on issues of Federalism which have relevance well-beyond that issue; put another way, Arizona dropped a deuce in our national punchbowl and all eyes were on Judge Susan Bolton's courtroom this week to see who might get splashed.

Lyle Denniston reported the result:

The constitutional fight over Arizona’s new alien control law appeared Wednesday to be headed toward higher courts after a federal judge in that state blocked four significant parts of the law from going into effect as scheduled early Thursday. Enforcement of a number of other sections was allowed — partly because the U.S. government did not challenge some, and partly because its attempt to stop others was rejected by the judge. Whether the dispute will reach the Supreme Court is not yet clear.Denniston subsequently reported the State's appeal of Bolton's ruling to the Ninth Circuit and the appellate court's determination to hear the appeal in the normal course of its business, rather than on an expedited schedule as the parties had requested.

....

At this point, the blocked sections of the law have not been struck down; rather, they are simply on hold while the constitutional case proceeds in U.S. District Court.

....

Judge Bolton stressed that she would not block enforcement of the new law in all of its parts, as the Justice Department and civil rights groups had urged her to do. The law itself provides that, if any part is struck down, other parts can remain in operation. That, plus the fact that some of the new law simply changes existing law, led the judge to conclude that she had to analyze the measure section by section.

....

Among the more controversial parts that may go into effect is a new law giving Arizona residents a right to sue any state official or agency adopting a policy that would lead to lax enforcement of federal immigration laws; such a lawsuit would assert that the official or agency had failed to work for enforcement to “the full extent” of federal law.

Another provision that she allowed to go into effect would create a crime to stop a car or truck to pick up day laborers and for day laborers to get into a car or truck if that would interfere with normal traffic movement. Bolton also did not block four separate provisions that add to existing law that makes it a crime to knowingly keep an illegal alien on the job, to to intentionally hire an illegal alien. Also allowed was a change in present law that requires businesses or others hiring workers to check on their eligibility to be hired. While the government’s lawsuit against the Arizona law also challenged a change in state law that already makes it a crime to engage in “human smuggling,” the Justice Department told the judge it was not seeking to block that section at the present time.

Offering what he described as "very preliminary thoughts" on the injunction decision, Orin Kerr noted:

Judge Bolton construes some of the vague provisions of the Arizona law; concludes that those sections are inconsistent with the general concerns underlying the federal immigration policy; and then she blocks those sections from going into effect.Kerr's co-Conspirator, Jonathan Adler, touched-on the importance of this case beyond the narrower immigration policy questions:

....

Given that parts of Judge Bolton’s opinions are based on a statutory interpretation that the lawyers for Arizona themselves rejected, I would guess there is a possibility that this opinion may ultimately lead the Arizona legislature to pass amendments to the Arizona law clarifying some of the sections. But that’s just a guess.

Bolton held these provisions are preempted by federal law, not that Arizona’s law is discriminatory or otherwise unconstitutional. The Court could have held that portions of Arizona’s law intrude upon the federal government’s exclusive authority over immigration, but it did not. Indeed, it explicitly rejected this argument with regard to portions of the law, as it rejected the federal government’s dormant commerce clause argument. Instead, where the court found preemption, it was based upon actual or potential conflict with federal law and policy.William Jacobson suggested that the decision to prevent the Arizona law from taking effect, preliminary though it is, does nothing to resolve Americans' increasing frustration with illegal immigration and with ineffectual enforcement of existing Federal laws:

The specific preemption arguments accepted by the court appear to be quite broad, and it is unclear whether they are confined to the immigration context.

....

Some commentators are surprised that Judge Bolton rejected Arizona’s interpretation of its own state law, but this is not that unusual, in the preemption context or otherwise. Insofar as a federal judge finds the text of a state law clear, this text controls, state assertions notwithstanding. A state’s interpretation of its own law is due some respect, but it is not controlling. The same holds true for the federal government — the DOJ’s interpretations of congressional statutes do not bind federal judges.

At a legal level, it is true that nothing has changed. S.B. 1070 never took effect, so no law was lost.Paul Kennedy was as frustrated with the partial injunction, though for decidedly different reasons:

At a more realistic level, everything has changed.

States have been left helpless to deal with the anarchy created by the failure of the federal government to enforce border security. Whereas yesterday it was unclear how far states (such as Rhode Island) could go, today states are powerless.

The inability of a state to implement a policy of checking the immigration status even of people already under arrest for some other crime is remarkable.

....

With a federal government which refuses to take action at the border until there is a deal on "comprehensive" immigration reform, meaning rewarding lawbreakers with a path to citizenship, this decision will insure a sense of anarchy. The law breakers have been emboldened today, for sure.

It's good that the police have been enjoined from enforcing the more onerous sections of the law, but the law itself is still on the books. Not only that, but the attitudes among those in power in Arizona are still intact and they will continue to fight for SB1070 to the death. They will seek to destroy one of the bases of our justice system -- the presumption of innocence.The drama surrounding the Arizona ruling was plenty exciting for me; it seems that I have a rather low threshhold for excitement, however. Garrett Epps praised the "blessed tedium" of the proceedings:

For you see, SB1070 creates the presumption that anyone who isn't white is breaking the law and as long as SB1070 remains on the books - even if neutered - the presumption of innocence is violated.

Public reaction to the boringness of the case has understandably been disappointment. They wanted WWE Raw and instead got Montesquieu's Spirit of the LawsMeanwhile in Virginia, our spring of hope winter of despair summer of ennui continued. As Virginia sought to lop-off the head of Obamacare with the guillotine of... oh, nevermind. Amongst others, the State of Virginia dislikes the broad new Federal healthcare insurance mandate and has filed suit to overturn it; the Obama Administration and many legal commentators described the suit as "frivolous". A Federal judge in Virginia disagreed, as Lyle Denniston explained:

....

I can relate to the public disappointment, just as I relate to my students' fluttering eyelids. In Judge Bolton's opinion, the most important precedent relied on is Hines v. Davidowitz, a 1941 case in which the Supreme Court held that Pennsylvania could not require all non-citizens in the state to carry state alien-registration cards and display them whenever a policeman asked. The Hines opinion, by Justice Hugo Black, is dominated by discussions of the foreign affairs power, the Supremacy Clause, and Congress' plenary authority of matters of naturalization. But Justice Black also alludes to the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and warns that requiring aliens to carry papers would subject them "to a system of indiscriminate questioning similar to the espionage systems existing in other lands."

To me, that's the central question in United States v. Arizona: whether a state can single out a group of people for harsh restrictions, criminalize those who help or employ them, and require law enforcement personnel to sniff them out and demand papers. One doesn't have to be a fan of illegal aliens to believe that no one should be treated that way. I am a fan of judicial opinions that vindicate equality and dignity.

But I understand why those concepts are missing from a case that is almost certain to continue through a full trial on the merits, another District Court opinion, at least one appeal to the federal Court of Appeals, and one or more brushes with the Supreme Court.

....

The law's delay will damp down oscillations in the public mood and force the rest of us to reflect on what is really at stake in Arizona. It will bore us into civil virtue. That's not a criticism; that's high praise. I often think boredom is the major force that prevents people from killing each other on the streets. And when you want boredom, call the Bar Association.

God bless careful lawyers and good judges. No matter how interesting the times, they bore us and they bore themselves; they snooze for our sins.

The new law, the judge commented, “radically changes” health care coverage in the country. In passing it, he added, Congress broke new ground and extended “Commerce Clause powers beyone its current high watermark.” Both sides, the decision said, have turned up prior rulings, but they are “short of definitive.”Some days, "not frivolous" is a big win. Randy Barnett for one cheered the decision as such:

“While this case raises a host of complex constitutional issues,” the judge wrote, “all seem to distill to the single question of whether or not Congress has the power to regulate — and tax — a citizen’s decison not to participate in interstate commerce” — that is, a private decision not to buy health insurance. “Neither the U.S. Supreme Court nor any circuit court of appeals has squarely addressed this issue…Given the presence of some authority arguably supporting the theory underlying each side’s position, this Court cannot conclude at this stage that the [Virginia] complaint fails to state a cause of action….Resolution of the controlling issues in this case must await a hearing on the merits.”

....

The state’s complaint made two basic constitutional arguments: first, that Congress does not have the authority, under the Commerce Clause, to require an unwilling private person to buy something from a private source, and, second, that, since there was no constitutional basis for Congress to pass the mandate, the law cannot be upheld as a valid use of Congress’ authority to put a tax on that individual, under the Constitution’s Necessary and Proper Clause.

As an alternative, the state contended that its rights as a sovereign state under the Constitution’s Tenth Amendment are violated by the new federal mandate, because it conflicts directly with a new Virginia law — passed explicitly to set up such a test case — that protects the citizens of Virginia from any such federal health mandate.

Essentially, from day one, politicos like Nancy Pelosi and numerous law professors have been saying about the constitutional challenge to the individual mandate: “Nothing to see here folks, move along.” Today Judge Henry Hudson ruled, “there is something to see here folks, let’s stop and evaluate carefully.” That is a big step.Others also applauded the setback for Obamacare, including Stephen Bainbridge, who wrote, "It's very early days. A trial court decision on a motion to dismiss is hardly dispositive of squat. Having said that, however, this opinion sets a very good tone for the lengthy battles to follow." Ilya Shapiro added:

....

While today’s ruling by Judge Hudson did not decide the case on the merits, it did make at least one official ruling of importance: the constitutional objections to the individual mandate are serious and not frivolous. This is an essential implication of today’s ruling because, had they been frivolous, the motion to dismiss would have been granted. So, no matter what the outcome, today’s ruling vindicates the legal judgment of the Attorneys General of 2/5 of the states that there are serious constitutional questions about this claim of government power.

[I]t is a beachhead in the fight against big government. Judge Hudson’s opinion should finally silence those who maintain that the legal challenges to Obamacare are frivolous political ploys or sour grapes. The constitutional defects in the healthcare “reform” are very real and quite serious. Never before has the government claimed the authority to force every man, woman, and child to buy a particular product – and indeed such authority does not exist....It seems that there is a consensus amongst notable blawgospheric Ilyas on this matter; Ilya Somin analyzed the decision:

Hudson rejected the federal government’s claim that Virginia did not have standing to challenge the mandate. Although states are generally not allowed standing to litigate the interests of their citizens, Hudson argues that Virginia has standing because the federal health care bill conflicts with a recently enacted Virginia state law, the Health Care Freedom Act. This, he argues, is enough to give Virginia standing.... Hudson also rejects the federal government’s argument that the lawsuit isn’t “ripe” for adjudication because the individual mandate will not come into effect until 2014. He points out that the new federal law will force both individuals and the state government to make adjustments to their health insurance plans even before that.Jack Balkin was critical of the standing determination and suggested that it encourages states to make an end-run around a significant procedural hurdle and existing Federal law concerning tax protests:

The most interesting aspect of Judge Hudson's opinion is his treatment of the standing issue and the tax anti-injunction act. He argues that what Virginia really wants is to vindicate its own recently passed Virginia Health Care Freedom Act-- which asserts that no Virgina citizen may be forced to purchase health care insurance; that this law conflicts with the federal Affordable Care Act, and therefore Virginia has standing to challenge the act under the 10th amendment. Judge Hudson also argues that the tax anti-injunction act does not apply because Virginia might not be able to persuade anyone else to challenge the individual mandate, and nobody else might have standing to raise Virginia's Tenth Amendment claims.Whether or not the ruling indicates that Hudson's final decision on the merits of the case will go Virginia's way, Josh Blackman is in a mood to celebrate; he proposed a drinking game based on statements from Randy Barnett, a senior fellow of the Cato Institute who was involved in writing that group's amicus brief and who often speaks and writes about the constitutionality of the Obamacare mandate:

Judge Hudson recognizes that the Virginia Health Care Freedom Act is merely declaratory, but he argues that "[d]espite its declaratory nature, it is a lawfully-enacted part of the laws of Virginia. The purported legislative intent underlying its enactment is irrelevant." In essence, Judge Hudson argues that by passing a law that says that Virginia will interpose itself to protect its citizens from the individual mandate, Virginia has succeeded both in giving itself standing and in getting around the federal tax-anti-injunction act.

These arguments are the weakest part of the opinion, and in particular, the arguments about the tax anti-injunction act strike me as particularly weak. The fact that Virginia can get around the tax anti-injunction act simply by passing a statute saying that it thinks the federal law is unconstitutional means that every state in the Union can do so as well. This undermines the purposes of the tax anti-injunction act, which was to keep tax protesters from littering the federal courts with protest litigation; the act requires that challenges to tax laws proceed in an orderly fashion through requesting refunds.

....

Judge Hudson... has tipped his hand about the merits in the way he describes the case. He clearly sympathizes with the state of Virginia. First, he characterizes the challenge as a "narrowly-tailored facial challenge" (normally, one says this about as-applied challenges, not about facial challenges, which are generally characterized as broad based). Second he characterizes the issue as one of first impression, which is precisely what opponents of the individual mandate want. Third, he characterizes the issue as whether individuals can be forced to participate in interstate commerce, which also accepts the framing by opponents of the individual mandate. Fourth he massages a quote by a Justice Department attorney to suggest that the government is conceding that Congress would not have the power to enforce a tax penalty if the mandate "is not within the letter and the spirit of the Constitution." This is also the view of the opponents of the individual mandate, who want to merge the taxing power argument with the argument about the commerce power.

Randy Barnett’s argument with respect to the unconstitutionality of the mandate hovers around the notion of being unprecedented.... While liveblogging Randy Barnett’s address before the ACS on the constitutionality of the individual mandate, I proposed a Randy Barnett drinking game.

Drinking game. How many times will Randy say unprecedented?....

Unprecedented indeed. Take a shot for liberty. And I’m buying Randy a round.

As the population of the legal blogosphere changes over time, a few arguments recur periodically. One of these concerns the proper roles of the prosecution and defense and the nature of "justice" in the criminal law context. That discussion played-out again this past week, principally between John Kindley and Mark Bennett, with others joining-in here and there. Kindley wrote that a few more experienced criminal defense lawyers (whom he referred to as "self-styled real criminal defense lawyers") have been offended by his prior discussions about whether "justice" should be one of the defense's objectives:

I’ve suggested that we too, even more than prosecutors, are the guardians of justice.Mark Bennett suggested that Kindley's was a straw man argument and responded:

....

The RCDLs have made it clear why they think my idea is not only wrong but dangerous. (They think I might undertake the representation of a client and that the zealousness of my representation might be affected by whether I personally think the client “deserves” what the State is trying to give him.) So why do I think that the contrary idea is not only wrong but dangerous? Well, for starters prosecutors have been known to argue, or to try to argue, to juries that their job is to “do justice” while the job of the criminal defense attorney is merely “to defend.” Presumably, they wouldn’t make the argument if they didn’t think it would help the prosecution. That argument, when it’s been attempted, has been ruled improper. But if the “truth” of the prosecutors’ assertion is conceded even by defense attorneys, then it’s only to be expected that this “truth” will filter down to the public at large. The people who embrace this “truth” will sit on juries, and will be predisposed to trust the prosecutor and not us.

....

It’s understandable why “Justice” is a dirty word among criminal defense attorneys. It connotes “punishment” and “retribution,” when in fact the propriety (i.e. the justice) of punishment and retribution is itself open to debate. I myself see the merit in the argument that the desire for punishment and retribution is something we should excise entirely from our souls and our society, though I’m not persuaded by it. But Justice is simply people getting whatever it is they deserve. What exactly it is that people in general or a group of people or a particular person deserves is famously fodder for passionate disagreement. But the very fact that we are constantly trying to persuade each other that our sense of what we or other people deserve is right implies at least some faith in the existence of a common and objective touchstone.

We criminal defense lawyers humor prosecutors saying that they seek justice as we humor our mentally-disabled cousins: they're not hurting anyone, and correcting them would be a waste of breath. Besides, "seek justice" is a better lodestar than the alternative, "follow the law" (which principle is the engine that drives all governmental tyranny).In a subsequent post, Bennett spoke further about the elusiveness of "justice":

In substance, criminal defense lawyers seek not justice but freedom. Our job is to get as much freedom for our clients as we can.

Imagine a continuum, with life in prison without parole (or death) at ten and no government sanction at zero. In a particular case, the prosecutor has some number in mind—his idea of justice. The criminal defense lawyer (one who thinks we humans can tell what is just) might have some number in mind—her idea of justice. They could both be wrong. The just number could be higher or lower than both, or in between. Nobody—not the prosecutor, not the defender, not the judge and not you or me—knows.

I don’t sympathize with the position that there is no justice. I believe (because I want to, okay?) that there is justice, but it’s pretty clear to me that none of us humans know what it is. But, as the absence of injustice is not justice, so the existence of injustice doesn’t prove the existence of justice.Norm Pattis suggested that notions of justice and a defendant's factual guilt should be irrelevant to the defense function:

But how is it that we could have the capacity to know injustice without an equivalent capacity to know justice? I figure we don’t really know what anyone deserves. Any disturbance of the status quo might be just. The innocent man might well deserve, for some other reason unknown to us, to die. But killing him for the wrong reason—for the crime he didn’t commit—is unjust. In much the same way, due process is no guarantee of a just result, but punishment administered by the government without due process is intrinsically unjust.

All that’s not unjust is not just. That we have the capacity to identify injustice says nothing about our ability to know justice.

Whether a client has actually done what is alleged rarely crosses my mind when making a decision about whether to represent someone. It just does not matter to me. Law is not morals. I am not a priest or a psychologist. Killing may be against God's law, but I am not a member of the celestial bar. I presume God can take care of His own enforcement issues.Jeff Gamso agreed with Pattis:

I defend people accused of engaging in conduct prohibited by the state. The state defines the crime by way of legislative fiat. Prosecutors then seek to punish those they have good reason to believe broke the law. My job is to defend people from the state. In doing so, I am inspired by the conviction that the state, like any other human institution, is far from perfect: It makes mistakes, acts in fury, and is capable of waste.

....

It isn't a question of conscience, or a matter of morals. The state must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. Dicta in our cases say, and I believe, that it is better for ten guilty men to be set free than for one innocent person to be convicted. The reason for this is that a state that is too powerful is a danger to liberty. If the state wants to take anyone of us and put us in a cage, it should have to fight for the privilege. Otherwise, we will all find ourselves in cages of one sort or another.

Factual guilt is not legal guilt. A person can commit a heinous act but be not guilty as a matter of law. That happens when the state fails, for any of a number of reasons, to meet its burden of proof. When this happens, I am not troubled at all. I simply don't want an omnipotent or omniscient state governing me. Such a state suffocates.

Where does that leave justice? I am not a minister of justice. I defend people within the scope of the rules of professional conduct. Justice is not a goal I seek; rather, it is, if the system performs well, a product of a process of which I am but a mere participant. As a lawyer I do not pick and choose clients based on my conception of justice.

I'm a criminal defense lawyer. I advocate for the interests of my client because I've chosen that job (or maybe it chose me, but that's another discussion). I choose (we'll stick with that) to advocate for the interests of the criminally accused because at the end of the day, I think it makes for a better society to have what we euphemistically call the "criminal justice system" tilted strongly in favor of the criminally accused. The state has too much power, power that it readily abuses. One way to check that power, to rein it in, is to defend those against whom it is directed.

It doesn't matter, it's simply irrelevant, whether those people have actually done what the government claims they have.

....

I want safe streets. I want a community free of dangerous people whether they are criminals or cops or just folks who happen to be dangerous but without either position or formal accusation. But my job as a criminal defense lawyer is not to create, not even to enable that community. It's to hold back the government. It's the government's job to ensure - hell, nobody's ever put it better than the Preamble does. The job of the government is plain:

[T]o form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.That's a tall order. And it embodies conflicting goals. One is to "establish Justice," whatever the hell that means, but it clearly involves making up rules, which is a set up for trouble. Another is to "insure domestic Tranquility," which is something like working to see that the rules are followed and keeping us safe from bad guys. A third is to "secure the Blessings of Liberty." That's liberty against the government.

....

[T]here is a danger to his conflating the roles of justice seeker and criminal defense lawyer. It may not be a danger for John's clients, but it's a danger for the Republic. If the Preamble's goals are to have substance, they need all to honored and advanced, not conflated. One cannot simultaneously advocate for the people and for the state. Bennett pointed out the irony of Kindley doing that in a blog he calls "People v. State." That's exactly right.

In another post which made me glad not to be a criminal defense lawyer (as I once aspired to be) and doubly-glad not to be a criminal defendant, Gideon discussed a convenient legal fiction which adds to the deck stacked in the State's favor:

Consciousness of guilt is a neat little tactic employed by prosecutors and condoned by courts that seeks to cast every action taken by a defendant post-offense in a light most indicative of guilt.Scott Greenfield added his thoughts to Gideon's:

Did the defendant realize that the justice system is a mess and he was going to get convicted no matter how innocent he was, so he took off? Consciousness of guilt. Did he lie to officers because he mistrusts them? Consciousness of guilt? Did he decline to make a decision about whether to submit to breathalyzer until his spoke to his lawyer? Consciousness of guilt.

As you’re well aware by now, there is no presumption of innocence, just a presumption of guilt. And how does the court system solidify that presumption? By pairing it with the “guilty conscience”.

Juries routinely get instructed on “consciousness of guilt”. They are told to *wink wink* draw whatever inferences they may from the defendant’s post-offense or post-arrest conduct. But what if the tables are turned? What if there is some post-offense or post-arrest conduct that shows a defendant is not acting like a guilty person (whatever that may mean)? Of course not. Don’t be silly, this is the justice system we’re talking about. There is no such thing as “consciousness of innocence”, because innocent people don’t get arrested.

So if a defendant wants the jury to draw a favorable inference from the fact that he offered to take a polygraph, but the police refused to administer it, he’s out of luck. Or if the defendants wants to tell the jury to consider the fact that he voluntarily turned himself in (which, per the English language, is the opposite of fleeing), he can’t. If he wants the jury to draw whatever inferences they may from the fact that he asked to be submitted to a breathalyzer, he can’t, because dammit these are the rules we made and that’s that.

This is nothing more than a call for jurors to project their own assumptions, under the guiding hand of the prosecution, onto the actions of a defendant. It's really quite a bizarre trick, in that a defendant is placed in the most unfamiliar and stressful terrain of his life, where his brain races a million miles an hour and tries to figure out what to do, how to react, while the jury is allowed the opportunity to leisurely review the defendant's choices and called upon to decide whether that's the way they would react, given all the time in the world to come up with the best possible choice. Yet courts allow it. No, they encourage it.There's a considerable amount of chatter here and elsewhere about what people are doing wrong in legal blogging; it's refreshing then when someone notes an instance of someone doing things exactly right. Eric Turkewitz is himself an example of how to do things right, but recently he mentioned a couple of others who set an example. Turkewitz discussed blogging newcomer (and personal injury attorney) Alan Crede's criticism of longtime tort reform proponent Walter Olson's forthcoming book and Olson's response:

....

Normal people project motivations on others all the time. And each of us is absolutely certain we're normal, meaning that anyone who doesn't do what we think they should are abnormal. Defendants often respond to the insanity and unfamiliarity of a police confrontation in strange ways. Afterward, when you ask why someone did what he did, you get a shrug. They realize later that they could have handled it better, whether it's keeping their mouth shut or not struggling as they were being cuffed. For whatever reason, be it fight or flight, or maybe an assertion of misplaced dignity, their conduct will come back to bite them in the butt. It does not mean, however, that it's evidence of guilt, conscious or otherwise.

It's evidence that most people don't know what to do when confronted by police. Nervousness is one of the most prevalent assertions by police in describing a defendant's reaction to what they characterize as a simple question. Do you know anyone who isn't nervous when confronted by police? Whether criminal defense lawyer, judge or street punk, of course we're nervous when some guy with a gun and undetermined intelligence commands us to do something. Only a fool is comfortable.

The prosecutorial reaction to such complaints is that the defendant is always free to take the stand and explain himself, clear up the mystery of his seemingly guilty conduct. This is a straw man argument, as there are a thousand considerations that go into putting a defendant on the stand having nothing to do with explaining away the facile inferences. Prosecutors know this, and argue it largely to goad the defense so that they can bring in the defendant's prior criminal conduct, unpleasant disposition or confused demeanor on the witness stand. Unlike police, defendant's don't take classes in how to testify convincingly at the defendants academy.

[W]hereas most bloggers would ignore such criticism, or silently fume, Olson links to it, showing the other side of the coin to consider. Crede’s points may be good, or not, but it is for the reader to decide.Civility amongst attorneys with competing professional interests can be difficult to achieve in the blawgosphere or outside it, as Jamison Koehler discovered at a recent continuing education event:

Not too shabby. And a damn good lesson for new bloggers trying to understand how the blogosphere works in its many interlocking ways. Good bloggers don’t view the visitor as a one-shot deal, but as a recurring reader. If you write well and provide quality links when deserved, the readers come back. Google made its fortune, its worth noting, by sending people away from its site.

Take note also that Crede “gets it” with respect to blogging, as he likewise linked to Olson’s sites....

The Virginia Bar seems to take special pride in the civility of its lawyers. Some of the court behavior that lawyers get away with in other states – the contentiousness, the tricks — is not tolerated in Virginia. “Honest,” “truthful,” “respectful,” and “pleasant” were among the words people used to describe this special breed of attorney.Going the whole nine yards in promoting civility and collegiality amongst members of the bar, this past week Koehler announced the formation of a fantasy football league amongst criminal law bloggers. There's no word yet whether the playing field will be level.

I was very pleased to hear all of this because, right or wrong, I pride myself on these very qualities. Hey, I thought, I’m golden. That was, of course, until I went to the afternoon breakout session for criminal law attorneys.

....

By the time we got to the session’s final hypothetical situation, a scenario involving the prosecutor’s duty to turn over evidence during discovery, the county prosecutors from Fairfax County were glaring at me from across the room. The feelings were reciprocal. So much for civility and respect in Virginia.

....

“There is no pretrial order in place requiring any designation of proposed exhibits until the eve of trial and counsel has made several specific discovery demands informally to which [the prosecutor has] simply responded that ‘it’s all in there somewhere.’” The question posed for discussion: Does this statement fulfill the prosecutor’s obligations or should the prosecutor alert the defense lawyer to the relevant pages.” (The problem did not specify whether the relevant pages were clearly exculpatory or not.)

One of the prosecutors jumped in to answer the question. While I can’t remember exactly what she said, the thrust of it was that the prosecutor in the hypothetical had “covered” himself by turning over the documents even if it was clear that the defense counsel would never be able to identify the relevant documents in time for trial. Another county prosecutor jumped in to agree with her. Hey, this guy said, the prosecutor did what he needed to do. Let the defense counsel find the documents for himself.

....

The next person to take the floor was a federal prosecutor from D.C., and he said everything I wanted to say. But he did it so politely, I am thinking he learned something from all the discussion about the Virginia way of doing things. He was also far more eloquent that I could have been.

Such an approach, he said calmly without looking at the other prosecutors, would be equivalent to not passing the documents at all. Besides, even if the documents had not been exculpatory (the hypothetical was unclear), why not point out the relevant documents to the defense attorney? What would you be trying to hide? And if turning over the information ruined the case, you probably shouldn’t be prosecuting the case to begin with.

We all kind of sat there for a second. The group leader nodded and the county prosecutors stared blankly. Yes, the group leader said finally. That’s the answer Bar Counsel gives.

Header pictures used in this post were obtained from (top to bottom) Carbolic Smoke Ball Co., Wikipedia, discovering urbanism, and Paris Odds n Ends Thrift Store.

No comments:

Post a Comment