When it comes to legal blogging, there seems to be no shortage of writing worth reading once one gets around to it.

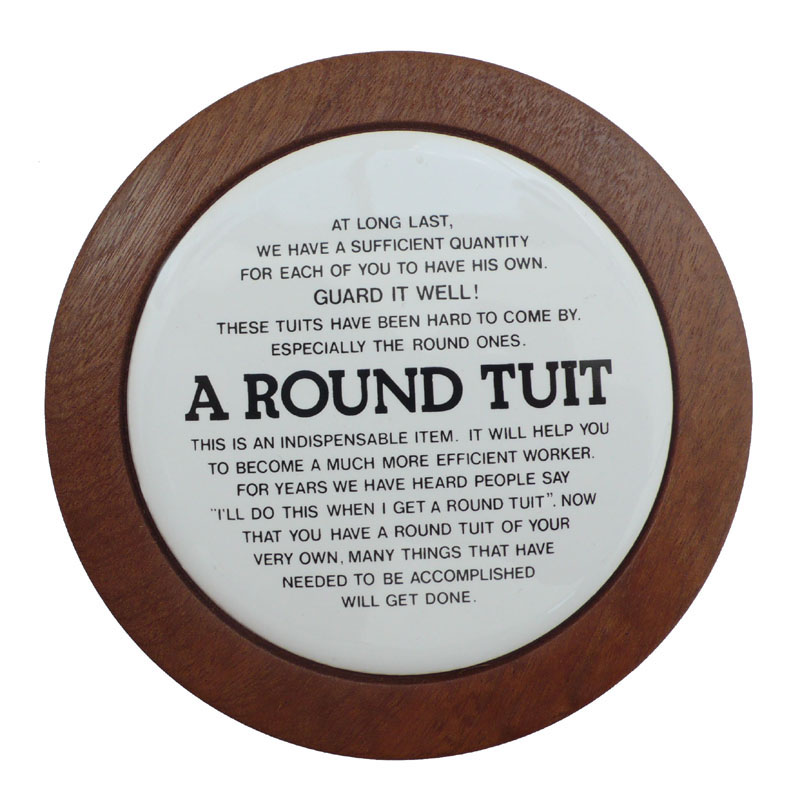

What's that? You have no round tuit? My friend, you are fortunate indeed, for never before in human history have round tuits been so readily available. If you need one, Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. has them in stock.

While you place your order, I'll share a few posts which are worth your attention.

It's October. The Mariners' bleak season has finally ended; the Seahawks' bleak season is yet to develop; my EPL fantasy soccer team is circling the bowl. No matter; the real games have finally begun.

The first Monday in October starts the Supreme Court's term and this term... will continue until the first Monday in October next year. That seems to be as much as the prognosticators can agree on, at least in the mainstream commentary I've seen over the past few days.

Fortunately, the legal blogosphere is generally a few cuts above the mainstream and it hasn't disappointed me this week — unlike the aforementioned Mariners, Seahawks, and EPL fantasy teams, but I digress.

Ashby Jones noted that his readership didn't need a reminder about the significance of the first Monday in October; he offered a round-up of some of the better mainstream press coverage of the new term, including articles on key cases and on the logistics of handling former Solicitor General Elena Kagan's elevation to Associate Justice. Bob Ambrogi and Craig Williams' long-running Lawyer2Lawyer podcast also took a look at the term ahead, focusing on a few of the more noteworthy cases the Court anticipates deciding during this coming year.

If there is a must-read source for information about the new term, it's certainly the much-redesigned SCOTUSblog site. Ahead of the opening day's arguments, James Bickford collected some excellent coverage and commentary, including a link to Nina Totenberg's interview with former Justice John Paul Stevens, who doesn't seem to regret his decision to trade his Supreme Court seat for a Barcalounger. The former Justice did admit one regret, however — his vote to uphold capital punishment in Gregg v. Georgia. As Mike Dorf explained, though, Stevens' regret is a nuanced one and might be somewhat misplaced:

In the interview with Totenberg, Stevens says that he expected that the sorts of factors upheld in Gregg would mean that only the worst of the worst would be executed, so that a death sentence would not be the sort of random lightning strike that Furman condemned. But, Stevens goes on to tell Totenberg, in the ensuing years the Court expanded the number of people eligible for the death penalty and otherwise changed the procedural law so that the assumptions underlying Gregg no longer held.Gideon had hoped that the Stevens-less Court might agree to hear Georgia death row inmate Jamie Ryan Weis' appeal, but the Court declined to do so:

....It's not entirely clear that Stevens has this right. The pro-death-penalty wing of the Court has argued that the lightning-strike character of the death penalty is due to the self-contradictory nature of the Court's death-penalty jurisprudence: Furman and its progeny require that the sentencer's discretion be constrained by aggravating factors, but Lockett v. Ohio, Eddings v. Oklahoma, and their progeny require that the sentencer have discretion not to impose the death penalty based on non-enumerated mitigating factors. Stevens was in the majority in both Lockett and Eddings, and if those decisions are the source of the failure of the Gregg assumptions, then he shouldn't be blaming the rest of the Court. But it's also not clear that the tension between Furman and Lockett/Eddings is responsible for most of the mess....

Georgia’s Supreme Court, by a 4-3 vote, did not find any problem with Georgia’s public defender system or the lack of funding or the fact that his lawyers withdrew and a new set of lawyers asked not to be appointed or….sigh.Noted Supreme Court observer Mike Sacks probably sees as much of the justices during the term as do their own families. He was off to an enthusiastic if damp start this term, sharing the sidewalk outside the Court with many others, including "FedEx Operations Manager and self-professed C-SPAN junkie" Graham Blackman-Harris:

And now a system that provides little to no adequate representation to those charged with and convicted of the most serious crimes with the most serious attendant penalty receives no Federal review. SCOTUS just denied cert. No explanation, no dissents, nothing.The stench has spread to Washington.

For a while now I’ve argued that these individual claims in State courts in individual cases will do little to bring the issue of systemic failure into the spotlight. That the only way to adequately challenge the failure to provide counsel is through lawsuits against the State (and maybe this latest legislation will help do just that). With this latest rejection by SCOTUS, it seems that Jamie Weis (and others) may have run out of all other options.

Forget doctoral students, forget stunt-bloggers, forget lawyers: Blackman-Harris truly embodies the civic passion so evident among the Court’s most ardent followers.On Monday, the Court requested seven case opinions from the Solicitor General's office. As Lyle Denniston noted, seven opinions is an unusually large number of requests for the Court to make. Very diplomatically, he declined to point-out that this was particularly inconsiderate, as the Court poached Justice Kagan from the Solicitor General's office, leaving them just a bit short-handed. Denniston reported:

....

This year, he showed up on a crutch, hobbled by hip problems. “I was going to crawl if I had to,” he says.

His commitment to his visits for First Mondays and landmark arguments runs deeper than mere interest. For this man from Jersey, it’s personal. “This is my Court!” he exclaims as we enter the building.

Graham Blackman-Harris, in his deep devotion to the American idea, proves how inconsequential everyday setbacks like injury or inclement weather really are to the success of the American spirit. From the Founders scrapping the Articles of Confederation for the Constitution during a stiflingly hot Philadelphia summer to our first African-American President’s inauguration on a frostbitten Washington winter morning, we and our leaders push forward against the elements into each new chapter in our country’s history.

Showing an interest for the first time in a case involving claims of torture during the “war on terrorism,” the Supreme Court opened a new Term on Monday by asking the federal government to offer its views on lawsuits against private contractors who work overseas for the U.S. military. The new case involves former Iraqi civilian detainees who had been held at the notorious Abu Ghraib prison that the U.S. military operated in Baghdad during combat operations there.Denniston also previewed arguments in the much-anticipated case NASA v. Nelson. I'll admit that I was somewhat disappointed to discover that the Nelson in question was NASA contractor Robert Nelson rather than astronaut Tony Nelson and the matter involves neither a mysterious woman nor an antique bottle. Regardless, Denniston explained that the decision in NASA v. Nelson may determine the scope of our "informational privacy" right (and would do so without the recused Kagan):

....

Among the other six cases, the government is to make recommendations to the Court on two securities class-action cases, a case about attempted recovery of art work stolen by the Nazis during the Holocaust, a case on the validity under federal law of a prison grooming rule that may interfere with inmates’ religious practices, a case about remedies for a chronic shortage of railroad freight cars, and a river water allocation dispute among three states.

The Supreme Court has recognized that the Constitution provides some protection for a right to keep private some personal information about one’s self — for example, medical information, financial matters, and sexual activity. But the Supreme Court has not closely focused on the scope of that right in 33 years. A case about the government’s power to seek access to some personal information, during a background employment or security check, puts the issue back before the Court — with the potential for a sweeping constitutional ruling, or a narrow one closely limited to specific facts.After yesterday's arguments, Denniston offered an early recap of the case's direction:

....

Among the factors that could have contributed to the Court’s willingness to step in without hesitation, two stand out: first, the government’s argument that the Caltech employees had made a facial challenge — the kind of constitutional complaint that a majority of the present Court seeks to discourage, and, second, the strong words of the Ninth Circuit dissenters that the constitutional right of information privacy had been broadly expanded and expressing a need for the Supreme Court to impose some restraint on lower courts in this field.

....

[I]t would be unlikely for the Court to use this case to make sweeping pronouncements on the scope of the constitutional right of informational privacy. The case very likely can be decided without doing so — as the government has suggested. The government, though, has made a strong pitch to confine the informational privacy right to one focused on potential dissemination, not on collection, of sensitive private data. That, in itself, would be a broad ruling.

The prospect of a 4-4 split in the case does suggest that the Court may attempt to decide it on the narrowest possible ground, in order to draw the votes of a clear majority of the Justices in order to get a definitive result. Among the narrower approaches would be to focus upon the government’s powers as employer. It also could give its own narrower interpretation of the breadth of the inquiries NASA makes, suggesting — at least by implication — that perhaps the inquiries might be re-worded to have less scope. And, the Court might accept the government’s view that this lawsuit does, in fact, amount to a “facial challenge,” and send it back for a potential trial on an as-applied claim, confined to the JPL employees alone.

Many of the Justices spent serious efforts during the one-hour argument... trying to determine just what the Constitution might say about the government’s authority to ask probing questions about highly personal and private matters — at least when it is asking them as an actual or potential employer of the individual being asked those questions.

There were, however, two Justices not joining in that pursuit. Justice Scalia suggested that the effort was inherently flawed; he argued that the Constitution says nothing at all about that subject, and so any restraint should be left to legislators, not judges. No one shared that view. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said the Court need not be making such a wide-ranging inquiry, since it was reviewing only a very specific and confined lower court decision restricting such questions. But most of the other Justices said — as Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., did at one point — that the Court had to have “some idea about either the existence or the contours” of the constitutional right in order to decide when it was violated by government inquiry.

The suicide of Rutgers freshman Tyler Clementi recently was a newsworthy tragedy as, frankly, many other young suicides and deaths aren't. I won't bother recounting all the public details of the events which preceded Clementi's jump to his death from the George Washington Bridge; they're public details after all, and if you're interested they're not particularly hard to find in any of the hundreds of news stories and posts discussing the suicide.

Kids without obvious talents or bright prospects, kids with drug problems or histories of legal troubles — those kids' deaths don't get the attention this young man's suicide did. For all the attention paid it, however, there seems to be much sympathy and little genuine understanding. Instead, an undeniable tragedy has become a platform for any number of generalized fears and causes du jour. He jumped because of bullying; we must prosecute his bullies and bullies everywhere. He jumped because he was bullied using newfangled technology; we must prosecute his cyberbullies and cyberbullies everywhere. He jumped because he feared being outed as gay; we must prosecute those who outed him and bemoan that our society is not more supportive of young gays. He was in college and something bad happened; colleges need to do more... something to prevent bad things from happening.

What characterized this tragedy more than anything else was the immediate and widespread vilification of the two classmates — Dharun Ravi and Molly Wei — who had the most direct involvement in the events which seemed to have the most immediate connection to Clementi's decision to jump. Yes, that's "seemed to" — no one really knows what prompted Clementi's decision. Collectively, we're unwilling to blame the young decedent for what is an inherently irrational, overwrought, and misguided choice, but unequivocally his choice; nevertheless, we have a need to blame and Ravi and Wei are handy targets.

Amongst the chorus of hyperbolic commentary, Elie Mystal did an admirable job of distilling a point which many others seemed to miss (probably willfully) — this may be a tragedy, a hurtful prank gone horribly wrong, but there's no crime here:

But here’s my question for all those who think Dharun Ravi committed a despicable act of bullying that should be punished to the full extent of the law: If Tyler Clementi hadn’t made the decision to take his own life, would anybody really care about the actions of Dharun Ravi? It’s not even clear that Ravi would have even been expelled from school, much less been charged with a crime punishable by up to five years in prison. This kind of stuff happens at college all the time, and the “but for” cause for this tragedy, if anything, is as much Clementi’s own decision as it is Ravi’s decision to spy on his roommate.In a second post, Mystal was even more critical of the efforts to prosecute Wei, who it seems did nothing more (or at least not significantly more) than allow a friend to borrow her computer:

....

[T]here are all kinds of laws you can break on America’s college campuses where the administration generally “looks the other way,” and we are (generally) fine with it. Underage drinking happens at college, illicit drug use happens at college, indecent exposure is a tradition at some colleges. There are all kinds of stupid and generally illegal activities kids do when they show up on campus.

I’m not saying that Ravi shouldn’t be punished in some way; I’m saying that a college freshman invading the privacy of another college freshman is hardly breaking news.

What makes it “news” is that Clementi killed himself. That’s tragic. But that was also his choice. Lots of kids get humiliated their freshman year of college. When I was at school, a girl did really crappy on her first set of finals, went home, and threw herself in front of a subway. That was sad, but I didn’t hear anybody calling on the university to relax its grading standards so fewer people feel compelled to end it all.

The other aspect of this story that has captured national attention is the fact that Clementi was gay, and the tryst Ravi exposed was homosexual in nature. But I’ve yet to see compelling evidence that Ravi did this because his roommate was gay. We’ll probably never know whether or not Ravi would have recorded the session if his roommate was hooking up with a girl.

Absent evidence of hate or even malicious intent, all I see is an 18-year-old who pulled a prank on his new roommate. If we’re going to punish him, fine. But let’s punish him as an 18-year-old prankster, not as a monster who stood next to Tyler Clementi and harangued him into jumping off a bridge.

Prosecutors looking into Tyler Clementi suicide indicated yesterday that they might not be able to charge Dharun Ravi and Molly Wei with a hate crime. Middlesex County Prosecutor Bruce Kaplan told the Newark Star-Ledger that his office was trying to see if they could charge Ravi and Wei with a second degree bias crime, but so far they don’t have enough evidence to support such a charge.Scott Greenfield noted the tendency of many in the blogosphere and elsewhere to capitalize on some aspect or another in the Clementi suicide to further their pet concerns:

Right now, Ravi and Wei are charged with invasion of privacy, which carries a maximum sentence of five years in jail.

Given that some people have pushed for prosecution that goes all the way up to homicide charges, the possibility that Ravi and Wei won’t be charged with a hate crime (or burned at the stake, or whatever the hell will satisfy people’s revenge impulse) will disappoint many — perhaps including prosecutor Kaplan, who said: “Sometimes the laws don’t always adequately address the situation. That may come to pass here.”

And sometimes the public’s outrage completely outstrips the actual crime committed.

The death of this young man is a tragedy. Whether this online airing of his private moment drove him to suicide, was the straw that broke the camel's back, somewhere in between or entirely unrelated, will never be known. The secret truth of Clementi's purpose died with him.Sure enough, within days, local politicians had leveraged Clementi's death and the public outcry to amend an existing cyberharassment law, broadening an already Constitutionally-problematic statute with even more questionable terms; Greenfield wrote:

It's fair to assume that Clementi's sexual preference, that the video of his encounter with another man, was a significant motivating factor. To use this tragedy to urge and educate about tolerance and sensitivity toward gays presents no problem, regardless of whether it's an accurate assessment or not. This is a worthy goal regardless of what role sexual preference played in Clementi's decision.

But to use this as a call to action for a new crime or enhanced punishment is an abuse of this tragedy. The abuse of tragedy to further irrelevant agendas has become so common that we barely notice anymore. We're particularly blind when we happen to like the disconnected agenda, happy to see any outcome, no matter how tragic and irrelevant, used to further a cause in which we believe.

This tragedy has also been seized upon by applying the pejorative "bullying" to it, despite a near total absence of connection whatsoever. Bullying has become a trendy cause, both because it's a very real problem as well as a convenient shield to deflect criticism and responsibility, and a facile means to create victimhood whenever feelings are hurt. Vague notions like bullying, which are as easily derived from the sensibility of those hurt as those doing the hurting, have enormous potential for misuse.

But heck, Tyler Clementi is dead and we can't let that go to waste. Even though we still have no clue as to what really went through Tyler's mind, or Ravi's for that matter, the forces of disingenuity can't let a tragedy go to waste. They've got agendas to sell, and if they can find people stupid enough not to grasp their abuse of tragedy, they've got a winner on their hands.For Daniel Solove, the details we read about the events surrounding the Clementi suicide did not so much indicate an absence of (and need for) criminal penalties for similar situations as these showed a general lack of appreciation for the damage violations of privacy can cause:

Let's face it, when it comes to a tragedy like this, one that even touches vaguely related sacred cows, even relatively smart people jump on board, blinded by their adoration of underlying causes and happy to close their eyes to rational relationships. In other words, who cares if it makes any sense, as long as the spin serves your desired outcome.

Just wrap up your beef, your issue, your next petty offense, in a tragedy and a ribbon and only evil people could possibly oppose you. After all, we're just doing this for poor Tyler Clementi.

What is clear is that this case illustrates that young people are not being taught how to use the Internet responsibly. Far too often, privacy invasions aren’t viewed as a serious harm. They are seen a joke, as something causing minor embarrassment. This view is buttressed by courts that routinely are dismissive of privacy harms. It continues to persist because few people ever instruct young people about how serious privacy invasions are. Another attitude that remains common is that the Internet is a radically-free zone, and people can say or post whatever they want with impunity.Crista Livvechi also discussed the degradation of privacy and suggested that the consequences can be particularly dire for young people who are still discovering and are still uncertain about their sexuality:

But privacy is a serious matter. People are irreparably harmed by the disclosure of their personal data, their intimate moments, and their closely-held secrets. Free speech isn’t free. Freedom of speech is robust, but it is far from absolute. Today, everyone has a profound set of powers at their fingertips — the ability to capture information easily and disseminate it around the world in instant. These were powers only a privileged few used to have. But with power must come responsibility. Using the Internet isn’t an innocuous activity, but is a serious one, more akin to driving a car than to playing a video game. Young people need to be taught this. The consequences to themselves and others are quite grave.

Twenty or thirty years ago, those who were questioning, exploring, and experimenting had the ability to maintain their privacy. Not just because the technology we’re pointing our fingers at now didn’t exist then, but because there was a clearer sense of where the line between public and private actually was. New technologies are changing this, yes, but technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum.... [O]ur ideas about public and private have shifted. Slowly, we’ve allowed the private to become public.Mike Cernovich likened the public outcry over Clementi's suicide and the condemnation heaped on his roommate, Ravi, to the "Two Minute Hate" used by Big Brother and his Ingsoc party to keep the masses distracted and obedient; he wrote that it's time for us to disengage from the Two Minute Hate directed at Ravi and look inward instead:

....

If we want to prevent more suicides, if we really want to nurture and protect and welcome people into the queer community, we have to make a space that’s safe not just for those who know who they are, but for those who aren’t sure yet.

We embarrassed and ridiculed people, or we joined the mobs in laughing at others unlike us. Fortunately our victims did not kill themselves.

What if they had? Would our pranks had taken on a greater moral significance? Must we measure a boy's conduct based on his motives, or upon the consequences?

Or should we stop looking at this boy?

The Two Minute Hate is powerful because it's a distraction. We look at others - Us and Them. They are evil, and as long we we stare at them, the law of Us and Them states that we are therefore good.

....

Do you speak out against bigotry? When people oppose gay marriage, do you remain silent and polite, like a passive-aggressive beta? When instead you should say, "Get the fuck out of here with that homophobic bullshit."

Most of us dare not offend, and so we tolerate the intolerable. We say that opposing equal rights for gay is a matter of "reasonable dispute." We say that not because it's true, but because we lack to courage to stand up against hate and bigotry. We use politeness as an excuse for cowardice.

When tolerating hate, we create a culture that leaves an 18-year-old boy fearing alone and afraid.

The UK's notoriously broad libel law will soon be tested by a well-known legal blogger and a controversial political commentator. Sally Bercow, the wife of the current Speaker of the House of Commons and a political candidate and commentator in her own right, was threatened with a libel claim after she criticized an anti-immigration study in a televised appearance. Sir Andrew Green, head of MigrationWatch, the group which authored the study (though not the Daily Express article to which Bercow referred directly), demanded that Bercow apologize publicly for referring to his group as "right-wing" (it claims to be non-partisan) and linking the ideas expressed in the article and study to Nazism and Fascism.

The Index on Censorship site described the comments which Green found objectionable:

Commenting on a Daily Express story migration and youth unemployment, Bercow said the article grossly oversimplified the migration debate, and that such oversimplification was “dangerous propaganda”. She claimed that arguments linking immigration to unemployment had been used by fascists such as Adolf Hitler and British Union of Fascists leader Oswald Mosley. The Express article had quoted figures from a MigrationWatch study.Rather than issue the demanded apology and pay legal costs to avoid the libel case, Bercow retained David Allen Green, who writes at the Jack of Kent blog, and another attorney to contest the matter. Though Bercow is a somewhat divisive figure, observers on both ends of the political spectrum seem to acknowledge that her resistance to the MigrationWatch suit could be a much-needed test to curb Britain's "draconian" libel rules. The Heresy Corner blog wrote:

Bercow did not mention Sir Andrew, and made just a single reference to MigrationWatch in the allegedly libellous comment.

Not that I feel like defending the substance of her apparent remarks. Decrying anyone who questions the benefits of large-scale immigration as a right-wing extremist or Hitler fan is lazy and offensive. As a cheap debating point it's a wearingly familiar left-wing tactic. And of course it's Godwin's Law in action: when you start bringing up Hitler, it's frequently a sign you've run out of proper arguments.David Allen Green emphasized that he did not intend to try his case in the blogosphere, but took this occasion to discuss the need for libel reform:

Migration Watch is right to cry foul, and I can even sympathise with their frustration at hearing the accusation yet again, this time from the wife of the supposedly non-political speaker.... But to launch a libel action the basis of casual comments made during a little-watched newspaper review is ridiculous. For one thing, Mrs Bercow's comments were taken apart quite comprehensively by her fellow guest, Iain Dale, who made most of the points made by Migration Watch's solicitors. The group simply does not need to resort to the law to rebut the claims (which were, as Dale pointed out, "preposterous"). This action will very likely prove counter-productive, putting Migration Watch's sometimes questionable statistics under the microscope and drawing attention to the use made of their statistics by actual right-wing extremists.

Legal letters like this are basically attempts to extort money with menaces, the menace being the law of libel, which is draconian in fact but even more draconian in reputation. Lawyers calculate that recipients will be scared shitless by the prospect of a financially ruinous court action and meekly apologise. And pay the solicitors' generous "costs". More often than not, they do. It's a scam. And it's scandalous that the law continues to allow them to do so.

The most depressing aspect about the predicament of free expression in the United Kingdom is not that for so many statements there is someone out there who wants to "ban" them but that there are so many officials and servants of the state - police officers, prosecutors, libel judges, district judges, ombudsmen - who will casually supercharge such illiberalism with the coercive force of law.When the nearby fire department — which has no obligation to serve you — offers to do so for a nominal amount, do you: a) pay said nominal amount and enjoy that peace of mind you wouldn't otherwise have; b) decline to pay said nominal amount and live with the consequences of your choice, come what may; or c) decline to pay said nominal amount, burn some crap in a couple of barrels in your backyard, set fire to your house, and complain to anyone who'll listen that the fire department wouldn't save your house even though they helped your more-responsible neighbor who'd paid the optional fee. Of course, the answer is "C"; this is America, after all. Orin Kerr reported this lesson in Personal Responsibility 101:

....

It would be ideal to have, at a stroke, the United States' First Amendment guarantee of free speech introduced into the United Kingdom. That is not, however, practical politics.

But our "banning" culture in respect of free expression is not inevitable and can be reversed; there is no good reason why the first reaction of so many people to unwelcome statements is to get the law involved, and then there is no good reason for so many police officers, judges, and officials to allow them to do so.

So the libel threat against Sally Bercow is, for me, another example of something which is horribly wrong in our political and legal culture.

The 911 operator told [now-former homeowner Gene Cranick] that because he hadn’t paid the fee, the fire department would not respond. Cranick’s wife told the 911 operator that she would be willing to pay “whatever the cost” to hire the Fire Department to put out the fire, but was told that this was not an option. The Fire Department did not come out until the fire spread to a neighbor’s yard — the neighbor had paid the fee — and the firemen put out the neighbor’s fire but not Cranick’s.Kerr noted a lively debate about this "Pay-to-Spray" fire department over at the conservative National Review's online site, The Corner. Daniel Foster seemed to put a lot of stock in the distressed wife's promise to pay "whatever the cost":

According to press reports, the community is outraged that the Fire Department didn’t respond to Cranick’s call and save his house. But it seems to me that if you’re going to make an insurance program optional, the way to get the service is to pay the fee. It doesn’t make much sense to decline to pay for a service and then be upset when it isn’t provided to you.

I have no problem with this kind of opt-in government in principle — especially in rural areas where individual need for government services and available infrastructure vary so widely. But forget the politics: what moral theory allows these firefighters (admittedly acting under orders) to watch this house burn to the ground when 1) they have already responded to the scene; 2) they have the means to stop it ready at hand; 3) they have a reasonable expectation to be compensated for their trouble?Foster's colleague, Kevin Williamson, called him "100 percent wrong":

The counterargument is, of course, that this kind of system only works if there are consequences for opting out. For the firefighters to have put out the blaze would have opened up a big moral hazard and generated a bunch of future free-riding — a lot like how the ban on denying coverage based on preexisting conditions, paired with penalties under the individual mandate that are lower than the going premiums, would lead to folks waiting until they got sick to buy insurance.

But that analogy is not quite apt. Mr. Cranick, who has learned an incredibly expensive lesson about risk, wasn’t offering to pay the $75 fee. He was offering to pay whatever it cost to put out the fire. If an uninsured man confronted with the pressing need for a heart transplant offered to pay a year in back-premiums to an insurer to cover the operation, you’d be right to laugh at him. But imagine if that man broke out his check book to pay for the whole shebang, and hospital administrators denied him the procedure to teach him a lesson.

The city of South Fulton’s fire department, until a few years ago, would not respond to any fires outside of the city limits — which is to say, the city limited its jurisdiction to the city itself, and to city taxpayers. A reasonable position. Then, a few years ago, a fire broke out in a rural area that was not covered by the city fire department, and the city authorities felt bad about not being able to do anything to help. So they began to offer an opt-in service, for the very reasonable price of $75 a year. Which is to say: They greatly expanded the range of services they offer. The rural homeowners were, collectively, better off, rather than worse off. Before the opt-in program, they had no access to a fire department. Now they do.Though they're in the right, to avoid this sort of public outcry in the future there will be tremendous pressure on the City to either discontinue its rural service and protect only its taxpayer community within City limits, or to quietly advise its firefighters to assist anyone who blurts-out an offer to pay "whatever the cost" and make a futile effort later to assess and collect those costs. Either way it'd be a loss for everyone except the least responsible in the area.

And, for their trouble, the South Fulton fire department is being treated as though it has done something wrong, rather than having gone out of its way to make services available to people who did not have them before. The world is full of jerks, freeloaders, and ingrates — and the problems they create for themselves are their own.

If rural fee-based service is discontinued, the responsible folks — like the Cranicks' neighbors in this instance — will be left unprotected; if the fee-based service regularly aids people who don't pay fees, there's no incentive to pay those optional fees and, naturally, those won't be paid. If the pay-for-spray fire department becomes a promise-to-pay-for-spray department, everyone will lose out. The department will spend its dwindling resources futilely attempting to collect the high real costs of firefighting from a few individuals rather than spreading these over a larger population base.

Admittedly, there's not much of a current legal angle to this story, apart from Orin Kerr's discussion of it. I expect that situations like these will arise more frequently, though, as cash-strapped municipalities shed many traditional government functions and focus on those constituencies which bear its costs through their taxes. Where, as here, a government has no obligation to act but contracts to do so, it should be expected to bear the obligations it takes on and to receive the benefits of its bargain. The liability issues associated with the devolvement of traditional government services and the rise of fee-based services remain to be sorted, of course.

As Kerr pointed-out, the citizens of the County could contract for City-provided fire coverage for its citizens and assess the costs as taxes; it's declined to do so thus far. Instead, the City has not only offered its services to those outside its limits but has gone further, actively encouraging people to sign up:

“We are a city fire department. We are responsible for the City of South Fulton and we offer a subscription (to rural residents). If they choose not to, we can’t make them,” [City Manager Jeff Vowell] said.Frankly, in Obion County, Tennessee at least, I suspect that the problem of rural fire coverage is now a self-correcting one. I wonder how many people in the County — people who didn't sign-up for the longstanding South Fulton program despite the annual mailers and the follow-up phone calls — were at South Fulton City Hall soon after the Cranicks' fire with $75 checks in hand? More than a few, I'm guessing. I hope the rest never realize the consequences of their short-sightedness, just as I hope governments like the one in South Fulton don't accommodate it.

....

Vowell said people always think they will never be in a situation where they will need rural fire protection, but he said City of South Fulton personnel actually go above and beyond in trying to offer the service. He said the city mails out notices to customers in the specified rural coverage area, with coverage running from July 1 of one year to July 1 the next year.

At the end of the enrollment month of July, the city goes a step further and makes phone calls to rural residents who have not responded to the mail-out.

“These folks were called and notified,” Vowell said. “I want to make sure everybody has the opportunity to get it and be aware it’s available. It’s been there for 20 years, but it’s very important to follow up.”

Mayor [David] Crocker added, “It’s my understanding with talking with the firefighters that these folks had received their bill and they had also contacted them by phone.”

Header pictures used in this post were obtained from (top to bottom) Carbolic Smoke Ball Co., Imp Awards, Photobucket.com, and Paris Odds n Ends Thrift Store.

No comments:

Post a Comment