When it comes to legal blogging, there seems to be no shortage of writing worth reading once one gets around to it.

What's that? You have no round tuit? My friend, you are fortunate indeed, for never before in human history have round tuits been so readily available. If you need one, Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. has them in stock.

While you place your order, I'll share a few posts which are worth your attention.

There was a little terrorism thingy on Christmas Day, which you might've heard mentioned here and there.

On December 22, 2001, a Muslim extremist tried to destroy an airliner with explosives hidden in his shoes; the Transportation Security Administration ("Treating you like a terrorist in between coffee breaks since 2001") reacted by requiring travelers to remove their shoes during pre-flight security screenings in order to prevent anyone else from doing precisely the same thing in the future. This time around, after a Muslim extremist tried to destroy an airliner with explosives hidden in his underwear, it's a certainty that someone at the TSA was readying the "Please remove your skivvies" signage before someone else pointed out that seeing an entire line of Southwest Airlines passengers in the altogether would damage our national psyche more severely than al Qaeda ever could.

Nonetheless, in the wake of an embarrassing lapse in security, punishments must be meted-out — not to those responsible for the lapse, mind you, but to the traveling public. As Radley Balko observed, "TSA... equates hassle with safety. For all the crap they put us through, this guy still got some sort of explosive material on the plane from Amsterdam. He was stopped by law-abiding passengers. So TSA responds to all of this by . . . announcing plans to hassle law-abiding U.S. passengers even more." Brian Tannebaum was quick to note that the constant fear-mongering since the 9/11 attacks made such reactive regulation a foregone conclusion:

So over the holiday weekend some 23 year-old Nigerian student and son of a banker allegedly tries to blow up a plane bound for Detroit during the last hour of the flight. He fails miserably. And here come the buzz words - "Yemen," "Al-Qaida," "Terrorist."The latest round of TSA rulemaking idiocy was widely-discussed in the legal blogosphere this week, principally amongst the bloggers at The Volokh Conspiracy. After the government announced that its vagueness about new security procedures was meant to make things more "unpredictable", Jonathan Adler was critical:

He'll be tried, convicted and sentenced to life. That's the beginning and end of the discussion of the criminal defense angle of this story.

As more information was learned this weekend, more buzz words - "blankets," "pillows," "no taking a leak within one hour of landing."

....

Now that's all gone.

Last hour of flight - no blanket, no pillow, and hold the bladder.

After spending the weekend hearing about this new "safety" policy, I finally heard someone say it - FOX's Greta Van Susteren said the policy was "almost insane." Fascinating to hear that on a network that spends most of it's time accusing the new administration of coddling terrorists and rolling back the War on Terrorism. The response to her comment was that a pilot thought it was done for the sole purpose of:

"Doing something."

And there we have it.

....

Our new policy of no blankets, pillows, or pissing in the last hour of flight, is that ridiculous. Why not include that Nigerian students that have bankers as parents are prohibited from flying?

On a holiday weekend where we were led to believe we were again "unsafe," our leaders had to "do something." And they did.

Whether or not “unpredictable” security measures may keep would-be terrorists on their toes, they will be a supreme annoyance for frequent travelers, and I’m unconvinced they will do much to enhance the safety of air travel. Forcing people to sit for an hour or more with nothing on their laps? Are they serious? And if travelers are supposed to expect “unpredictable” security measures, how will they distinguish between legitimate security measures and arbitrary commands from TSA personnel?Orin Kerr wasn't convinced that these new TSA procedures would make things more secure, but he also wasn't dismissing them out-of-hand as "theater":

Airport security is already more show than substance. It’s an exercise of political theater that is supposed to make travelers feel more secure. I am unconvinced it even does that very well anymore, and from what I’ve heard thus far, the new measures are only going to make things worse.

I can’t gauge how effective airport security measures are, but I think there’s a concept driving them beyond “political theater.” The model seems to be that the bad guys will want to do the same thing over and over again if we let them, and that our best security response is to force them to switch tactics to something unproven and less likely to work. As a result, we tend to ban the things that were used in the most recent attack to make it harder to try that method again the next time.Ilya Somin didn't disagree with Kerr's comments, but he suggested that we probably should not be reacting so strongly to unsuccessful terror tactics:

[I]t’s certainly possible that the terrorists will repeat effective tactics that worked well the first time. However, the last several attempted attacks... don’t seem to have been well planned, and of course they failed despite the advantage of surprise. If anything, we should want the terrorists to try these dubious methods again, rather than giving them additional incentives to think of new and potentially better ones.Kerr cautioned against relying too heavily on recent experience rather than tackling the more difficult task of broader threat assessment:

The core problem is... the extraordinary difficulty of threat assessment. Assessing the terrorist threat requires us to figure out what an undetermined group of people with cultures and life experience totally different from our own might do in response to various policies enacted around the world using constantly changing technologies we barely understand enforced by a sprawling global bureacracy we can’t fully comprehend. That’s really really hard to do.Writing in Psychology Today, Shankar Vendantam discussed the problems of false positives and false negatives and suggested that we need to carefully consider how we strike a balance between the costs of terrorism security and terrorism itself:

The difficulty of threat assessment means that we often fall back on two proxies: ideology and our very recent experience. We fall back on ideology because it gives us easy shortcuts. It can tell us how much to trust the government, how much to fear the terrorist threat, etc., creating the illusion of familiarity that we interpret as guideposts to answering the unknown. We then do our best to fit in new evidence to confirm our preexisting views.

We rely on recent experience to gauge the threat on the dubious assumption that the near future will be like the near past. If we just had a recent attack, we assume we’re in for a future of a lot of attacks. If we haven’t had an attack in a while, we assume the threat has gone away.... [T]he tendency to legislate after an attack but not before it largely reflects the crutch of recent experience. When an attack is recent, the sense of the threat is higher and legislatures are ready to act: The instinct of “do something” is not just an abstraction, but rather an instinct do “do something about a specific threat” the public has on their minds.

False positives are the innocent people we target during anti-terrorism measures.... False negatives are the terrorists who slip through.... False negatives can have catastrophic consequences, but there are invariably many more false positives than false negatives, so the adverse consequences of false positives can sometimes be greater than the cost of false negatives....The term "security theater" was popularized by Bruce Schneier. He's discussed the concept many times, noting that of all the changes since the 9/11 attacks, only the reinforcement of cockpit doors and the heightened awareness of airline passengers to security threats have made any meaningful difference. He revisited "security theater" in a CNN essay this week:

When it comes to terrorism, a truly honest conversation would ask how many terrorist incidents a nation is willing to tolerate in order to maintain its highest values regarding civil liberties, or how many civil liberties it is willing to forsake in favor of security. The dishonesty lies in suggesting we can always reduce false positives and false negatives simutlaneously: That is sometimes possible (when you develop a perfectly accurate and risk-free screening tool for [terrorism]) but more commonly you have to trade one off against the other.

Given the human penchant for wanting our cake and eating it, too, it isn’t surprising our national debate over terrorism falls into predictable and polarized camps, where each side demonizes the other’s views.

"Security theater" refers to security measures that make people feel more secure without doing anything to actually improve their security. An example: the photo ID checks that have sprung up in office buildings. No one has ever explained why verifying that someone has a photo ID provides any actual security, but it looks like security to have a uniformed guard-for-hire looking at ID cards.Randy Barnett spent most of Monday stuck in his car, forced to listen to talk radio hash and rehash these issues; it seems that perhaps this painful experience inured him to the TSA's renewed commitment to traveler-hassling:

Airport-security examples include the National Guard troops stationed at U.S. airports in the months after 9/11 -- their guns had no bullets. The U.S. color-coded system of threat levels, the pervasive harassment of photographers, and the metal detectors that are increasingly common in hotels and office buildings since the Mumbai terrorist attacks, are additional examples.

....

When people are scared, they need something done that will make them feel safe, even if it doesn't truly make them safer. Politicians naturally want to do something in response to crisis, even if that something doesn't make any sense.

Often, this "something" is directly related to the details of a recent event. We confiscate liquids, screen shoes, and ban box cutters on airplanes. We tell people they can't use an airplane restroom in the last 90 minutes of an international flight. But it's not the target and tactics of the last attack that are important, but the next attack. These measures are only effective if we happen to guess what the next terrorists are planning.

....

Our current response to terrorism is a form of "magical thinking." It relies on the idea that we can somehow make ourselves safer by protecting against what the terrorists happened to do last time.

Unfortunately for politicians, the security measures that work are largely invisible. Such measures include enhancing the intelligence-gathering abilities of the secret services, hiring cultural experts and Arabic translators, building bridges with Islamic communities both nationally and internationally, funding police capabilities -- both investigative arms to prevent terrorist attacks, and emergency communications systems for after attacks occur -- and arresting terrorist plotters without media fanfare.

[W]hat security does exist seems to have deterred attackers from using prohibited means and forced them to search for ways around rather than through the system. Even the 9/11 attackers used permissible weapons–box cutters–rather then try to sneak prohibited firearms on their flights. And this was pre-TSA, suggesting that the airlines’ much derided private security measures “worked” as intended insofar as use of contraband weapons was effectively deterred and terrorists were forced to find legal instrumentalities with which to accomplish their attacks. (The faulty argument that government agencies would better prevent attacks was what led to [the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security].) Regardless of what you think of handguns on airplanes, it was much harder to execute 9/11 with box cutters than with a handgun. The strategy used by attackers worked on 9/11, not because of a failure of screening for weapons–as opposed to screening for unlawful combatants, which certainly did fail–but because crew and passenger response had not yet adjusted to deal with new threat of suicide combatants rather than hijackings. The new terrorist strategy failed on its fourth attempt that very same day when militia members on United #93 learned of the suicidal intentions of their attackers and took aggressive action. Hence, the almost immediate shift by terrorists to shoe bombs which cannot be thwarted as easily by passengers and crew rather than suicide hijackings. So far as I am aware, no terrorist attacks have been committed, or even attempted, using prohibited weapons; nor have any attempts been made with explosive devices using liquids since liquids were banned. These security measures have thereby forced terrorists to use powder explosives hidden in underpants, an apparently a trickier technique to execute. Referring to them as mere “theater” — tempting as it may be — is misleading.Regardless the effectiveness of any new screening procedures the TSA might implement as a knee-jerk reaction to this latest incident, air travel will assuredly become (more of) a chore to be undertaken only when we have no other alternative. Am I the only one who suspects that the airline industry has already prepared their bailout request to defray any revenue losses remotely attributable to consumer reticence after the Christmas Day incident or frustration with the freshly-abusive... oops, I mean vigilant TSA? So where does all this leave us? It's a catch-22 — if we do not continue to fly, the Islamic terrorists will win; if we do continue to fly, the terrorists who run the airlines will win. Oh well, at least we can take some small comfort that we're not only ones who have had and will have wretched air travel experiences. The Iowahawk blog published a guest essay from the Christmas Day terrorist himself; it seems that his week didn't improve much after the failed bombing:

The fact that our declared enemies will look for ways around any screening protocol is perfectly predictable and an argument for focusing on personal screening to identify unlawful combatants before they get on a plane. It is an argument for treating terrorists as unlawful combatants rather than criminal defendants if for no other reason than they can be interrogated for intelligence about future attacks and techniques. It is also an argument for offensively carrying the fight to the enemy rather than solely relying on purely defensive measures to stop terrorist attacks....

But the fact that, until they are defeated, our avowed enemies will seek ways around current screening methods does not make these security measures mere “theater.” To the contrary, it presupposes that current screening is working to the extent such screening can ever work.

Yesterday while I was lying in the burn ward getting my crotch bandages changed, I had a chance to catch the air disaster movie marathon on TCM. The lineup included "Zero Hour," "The High and the Mighty," "Skyjacked," and "Airport '75." For all their campy fun and unintentional laughs, those corny old films really serve as a grim reminder how the whole in-flight terror experience has gone completely downhill since the jet set golden years of the 50's, 60's and 70's. What happened to all those pretty stewardesses and polite, well dressed infidels, screaming as the plane plummeted to the ground? Time was, a suicide mission to explode an international jumbo jet was an event full of glamor and excitement; but now it seems to be a endless series of delays, hassles, pushy jerks and third-degree testicular chemical burns. And don't even get me started on the crappy airline food.Somewhat more seriously, Ilya Somin suggested that perhaps over-emphasis on airline security (setting aside for a moment questions about its effectiveness) may be counterproductive in terms of securing us against terrorism more generally and preserving life overall:

In Europe and Israel, the terrorists have reacted to improvements in airport security by attacking trains, subways, university campuses, and other areas where large numbers of people gather in places that are harder to secure than airports and planes. That doesn’t mean that we should have no airport security at all. But it is a factor that weighs against adopting extremely costly and/or highly intrusive security measures. Even if such policies reduce the risk of terror attacks on planes, they still may not be worth their cost because they might fail to reduce the net loss of life caused by terrorism overall.Eric Posner also suggested that we're over-emphasizing airline security and that, moreover, our security expectations are too high:

Similarly, if we impose too many hassles on airplane passengers, more people will travel by train or bus, both of which are much easier for terrorists to attack than aircraft are. Others might choose to make long trips by car. Cars rarely make good targets for terrorists. But traveling a given number of miles by car exposes you to a much higher risk of death or injury by ordinary accidents than traveling the same distance by plane. Again, the net impact might actually be to increase loss of life rather than reduce it.

At the social optimum, the number of successful terrorist attacks will be greater than zero. It might be argued that we have had too few successful terrorist attacks over the last few years rather than too many. The question is whether the implicit statistical valuation of life in TSA programs is too high. I suspect that the answer is yes, as is generally the case with airline safety."Morally uneasy?" Hah! David Bernstein laughs at your moral uneasiness; he writes that it's long overdue that we get serious about terrorism and advises that, in addition to smarter security, we rework our immigration policies using the lessons we've learned over the last decade:

Profiling is an effective strategy when, as here, terrorists come from a small group of (relatively) easily identifiable people. One suspects that this explains Israel’s success. But profiling places a large portion of the cost of deterrence on a small group, which makes some people morally uneasy.

Number one on my list would be cutting off immigration from countries where jihadist ideology is popular. Several recent arrests involving home-grown domestic terrorists involve individuals whose families immigrated to the U.S. from countries like (IIRC) Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen. This should not be a big surprise. Immigrant youths and young adults often feel dislocated and alienated from their new society, and it’s not terribly surprising that some fraction of them would be attracted to extremist ideologies popular in their homelands, and readily accessible via the Internet.

[T]he vast majority of immigrants from these countries are perfectly law-abiding and will make fine citizens. But the question is, why take the risk regarding the small fraction that will turn out to be murderous terrorists? What’s the advantage to the U.S. of, say, taking in another ten thousand Somalians instead of, say, Salvadoreans, or Koreans, or Irish, or members of other nationalities that are far less likely to be implicated in anti-American terrorism? Assuming a finite level of overall immigration, it’s just common sense to prefer immigrants from more friendly societies.

....

The only reason I can see for NOT implementing draconian restrictions on immigration from countries that disproportionately produce anti-American terrorists is political correctness, in this case the pretense that a young immigrant from Chile is just as likely to try to blow up an Amtrak train as a young immigrant from Yemen. It’s time to get past such nonsense.

In Maricopa County, Arizona, the showdown between the judiciary and the County sheriff has long since passed the crisis point. Several legal bloggers have urged lawyers in the region to stand up for the courts and the rule of law, against the increasingly-lawless sheriff and his toadies. Finally, the local legal community has begun to act. Led by a local attorney, Jim Berlanger, several hundred lawyers and others demonstrated to show support for those standing against the sheriff's above-the-law regime; Mark Bennett interviewed Berlanger afterward. Sheila Polk, County Attorney for neighboring Yapavai County, published a blistering op-ed piece in the Arizona Republic newspaper:

Maricopa County is not my jurisdiction, but I can no longer sit by quietly and watch from a distance the abuses of power by Sheriff Arpaio and County Attorney Andrew Thomas.Scott Greenfield, who had been amongst the most vocal in calling for Maricopa-area attorneys to act, was quick to praise Berlanger, Polk, and the many others who stood up this past week and just as quick in condemning the continuing lack of concern shown by professional organizations like the American Bar Association:

I am conservative and passionately believe in limited government, not the totalitarianism that is spreading before my eyes.

The actions of Arpaio and Thomas are a disservice to the hundreds of dedicated men and women who work in their offices, and a threat to the entire criminal-justice system.

Peace officers and prosecutors take an oath of office that is sacred. We swear, under God, to support and defend our Constitution and our laws against all enemies, foreign and domestic. We also swear to "impartially discharge the duties of the office."

Our power, granted to us by the people, is not a personal tool to target political enemies or avenge perceived wrongs.

Prosecutors are ethically bound to refrain from prosecuting a charge that the prosecutor knows is not supported by probable cause.

In maintaining public safety, each of us is tasked, by our oath, with protecting the rights and privileges of the least among us. Everyday, in every single thing we do to keep our communities safe, we must respect the rule of law and the protections set forth in our Constitution.

Abdication of these responsibilities causes erosion of confidence in law enforcement and our communities become less safe.

....

Andrew Thomas and Joe Arpaio have strayed from their constitutional duties.

What we have witnessed over the past month are acts of increasing boldness and bravery. True, it was long past due for these acts, but they come in their own time. I'm sure when Jim Belanger called for a rally he had no idea that Sheila Polk would speak out in support of his purposes. Polk saw the opportunity and seized it, placing herself squarely on Crazy Joe's enemies list. She joined the tenor of Maricopa lawyers, bringing a beautiful soprano to the harmony.Jeff Gamso also commended Berlanger and Polk for their stands and wondered why, considering the propensity of the sheriff and his allies to single-out their critics for legal and extra-legal abuse, the federal government hasn't shown any inclination to involve itself; now that, after seeing her very public criticism, the sheriff has asked the FBI to take a look at Polk's actions, Gamso asks whether the feds will work for or against the sheriff:

Up to now, there are two common threads the bind those who have spoken out. A respect for law and the Constitution, and a willingness to accept the risk of Crazy Joe's ire. The latter is not inconsequential, given the fact that Arpaio is in command of an armed force and has shown no reluctance to abuse his authority to silence his enemies.

....

The ABA Journal has been busy running beauty pageants designed to get lawyers to register with its website, and pretending that marketers and social media gurus are Legal Rebels. This would be embarrassing enough on its own, palpable demonstrations of how vapid and superficial the ABA has become. They are selling a Legal Rebel skateboard, for crying out loud.

We could happily overlook its efforts to achieve pseudo-coolness if only the ABA Journal had seized this opportunity to actually serve a purpose, to take a stand, a firm, clear and forceful stand, at this point in time when it meant something. Not tomorrow or next week, after the brain trust figures out that their failure to stand up has made the ABA the embarrassment of the legal world.

By the mere act of having written about this event, while failing to either recognize its importance or take a stand, the ABA Journal, and thus the ABA itself, has shown itself to be irrelevant. Go run another beauty pageant or skateboard sale. That's all you're good for. The time to act has come and gone. It failed.

It's true that Sheriff Joe and his minions weren't at the rally with fire hoses or tanks. As far as I can tell, nobody was arrested or roughed up. All to the good. But the truth is that Joe and his poodle won't be stopped. Maybe it's just so ingrained they can't help themselves. Nah. It's choice. Criticism of them carries a price.Mark Bennett didn't hesitate to call out those attorneys who continue to work for Maricopa County Attorney Thomas, including those who criticized their boss but only in confidence to reporters:

So we come to Sheila Polk who is about to learn that lesson.

....

Prosecutors simply don't engage in this sort of attack on other prosecutors without cause. Or without thinking about the consequences. And they came quickly.

....

This isn't subtle. But what happens next? What if Polk doesn't stop? Do they send someone out with a baseball bat to break her kneecaps?

The feds seem singularly unwilling to take on the Arpaio/Thomas machine. Will they do that machine's dirty work?

For tyranny to succeed, good people must cooperate. The abuse of power to intimidate and punish judges for not toeing the executive’s line is a tool of totalitarians. Those prosecutors in Thomas’s office who privately revealed their feelings about this abuse to the Phoenix New Times are not just doing nothing. By continuing to work for Andy Thomas, and speaking out only privately, they are actively helping evil to propagate.The specifics of the Maricopa County crisis are — thankfully, for now at least — peculiar to Maricopa County; notwithstanding, courts throughout the nation are beset by a crisis of justice, as Gideon explains in this wake-up call:

....Cooperating in the subversion of democracy by undermining the rule of law might well be indefensible in a way that cooperating in one’s own debasement as a human and a professional is not.

Aside from the ethical question, there are practical considerations. These Maricopa County Assistant County Attorneys, casting their lot with Andrew Thomas, are lying down with dogs. If Arpaio and Thomas’s fantastical castle in the sky comes crashing to the ground, those lawyers are going to be remembered as having helped Arpaio and Thomas try to destroy the American system of government in Maricopa County. If Arpaio and Thomas’s delusions of grandeur are proven true—if the judiciary in Maricopa County becomes a lapdog or a nullity—those lawyers will be remembered as having helped Arpaio and Thomas succeed. Neither is a cheerful prognosis for their future outside of a totalitarian future; either way, Maricopa County’s Assistant County Attorneys wake up with fleas.

The economy may or may not be recovering, but one thing is for sure: budget deficits are spiraling out of control. Crime may be down, but the workload of the criminal justice system is up. In particular, the burden on public defender systems is one that has rarely been seen before.Scott Greenfield agreed with Gideon's assessment and highlighted one aspect in particular — the cascade effect lengthy sentences have on overall enforcement resources:

Whether this is a product of reduced funding, of lengthy sentences coming home to roost, of a zero-tolerance “tough on crime” policy enacted years ago or of the sheer overcriminalization of our society is an open question.... [W]hen books are written warning us that we commit three felonies a day, it’s time for someone to sit up and take notice. And by someone I mean those with the power to change the direction we’ve gone in: legislators and voters. So you, all of you.

The repercussions of too many people in the justice system are beginning to reverberate throughout the country....

....

This will not end anytime soon and even if there is an alleviation of the financial crisis, the impact on the criminal justice system will be temporary. More crimes will be committed, more knee-jerk reactions will be induced and harsher sentences will be given out. The burden continues to build until there is a fundamental change in the way we think about the numbers, the crimes and the system.

As Gideon contends, the years have brought us ever-increasing sentences, with ever-increasing costs. This followed the "tough-on-crime" trend that was borne of a sense of public frustration largely fed by politicians and media who were busily sensationalizing crime and manipulating the public fear to their own advantage. Sentence inflation, at best, is palliative, making us feel better without actually improving our safety or the system, and without anyone giving thought to the costs incurred. This doesn't touch, by the way, the collateral issue of defendant's leaving prison drug free and capable of gainful employment, another sore spot.Finally, in a very sobering post, Norm Pattis looks forward somewhat grimly to "another year in the trenches", defending the accused in a troubled justice system:

Gideon is right. It's time to scrutinize the bizarre and inexplicable sentences imposed, to terms of 17 years or 23 years or 8 years, and ask what conceivable basis could there be that would compel a judge to sentence a defendant to such an odd length of time. Every year beyond that which is necessary is a cost society, nor a defendant and his family, should not be forced to bear. We all suffer from these absurd sentences, and their whimsical imposition must be brought under control.

Summoning fight is usually not hard for me. I was born on the other side of the tracks and know firsthand how thin the line that separates me from the folks I represent. And for all my bold irreverence, I know a truth Christians know: All have sinned, and fallen well short of the glory of God.

But I am having a hard time summoning fight just now. I am tired, discouraged and filled with misgivings about the law and my role as a lawyer.

....

I did not count on becoming a friend of sorrow. Or fatigue. Or seeing clients put guns to their heads to avoid the consequences of a judge's scorn. Or mothers kneeling at my feet holding my hands weeping in a crowded hallway and begging me to do something for their son. Or responding to emails telling me how hard it was to keep from swallowing a jar of pills to make the night go away. I never thought I'd see so much suffering. I thought I would be able to prevent it from happening or make it stop. I thought I would be a hero.

But no one is a hero to a client spending his life behind bars.

....

When the law beckoned, I assumed it would mean a life of toil. But somehow I never really foresaw how hard the work would be. I see it now. And at once my knees tremble, and I know something I have not felt so powerfully in a long time: fear. A new year dawns and I am still bruised by the year just passed. Another year dawns and uncommon cunning is required yet again, and faith, too; yet I lack faith.

The law is hard; I must, somehow, become harder than sorrow.

This being the end of the year, many sites posted "year in review" or "best of" lists. I'll confess that I can't get enough of these things; I even read the ones compiling topics in which I have no interest the rest of the year (though I promise not to inflict any of those on you here).

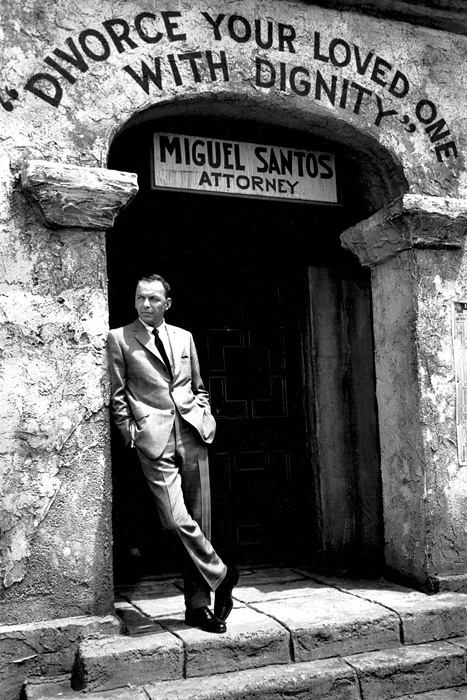

John Bolch's roundup of the year in divorce matters around the world was both concise and entertaining. If divorce was always this much fun, I'd probably be on my fifth marriage. If you're looking for reading material, in Forbes magazine Dan Harris published a list of the ten best books on China (that's PRC, folks, not Wedgwood). Kashmir Hill ranked the top five motions of the year, including a Motion to Compel State's Attorney to Drop His Accent (the accented attorney in question being the British-born blogger at D.A. Confidential) and a Motion to Compel Defense Counsel to Wear Appropriate Shoes at Trial. Charon QC gathered his wonderful F*ckART paintings (including my own treasured Fuckerflies III, pictured at left) into a single gallery.

John Bolch's roundup of the year in divorce matters around the world was both concise and entertaining. If divorce was always this much fun, I'd probably be on my fifth marriage. If you're looking for reading material, in Forbes magazine Dan Harris published a list of the ten best books on China (that's PRC, folks, not Wedgwood). Kashmir Hill ranked the top five motions of the year, including a Motion to Compel State's Attorney to Drop His Accent (the accented attorney in question being the British-born blogger at D.A. Confidential) and a Motion to Compel Defense Counsel to Wear Appropriate Shoes at Trial. Charon QC gathered his wonderful F*ckART paintings (including my own treasured Fuckerflies III, pictured at left) into a single gallery.In a bit of year-end wisdom, Dave Hoffman offered an observation about an "Eternally Contingent Truth":

[L]egal analysts left and right agree that the Constitution creates procedural structures (the senate, the bill of rights, etc.) that need to be modified in light of modern challenges; that the Supreme Court ought not have the final word of what it means for a law to be constitutional; that we need to really worry about executive overreach; and that data – not bias – should drive public decisions on problems like global warming and torture.That wasn't the only eternal truth discussed this week in the blawgosphere; another is that "the perfect is the enemy of the good". Dan Harris explained that if you have a "perfect" contract that you'd like to use in China, you may want to rethink your approach:

The nitpicky fact that left and right don’t hold these truths as self-evident at precisely the same moment in time seems trivial, right?

Sometimes our clients consider the perfect contract to be one that just really really protects them. In every single way. Late delivery? Chinese company has to pay a massive amount in liquidated damages? One item out of one hundred not quite up to snuff? Again, the Chinese company has to pay liquidated damages well beyond any possible harm to our client. Payment by our client? Payment by our client? Ten percent now, the rest upon delivery and confirmation of quality. Oh, and the Chinese manufacturer must not make any even similar product for any other company.Over the past year or so, "if you're thinking of becoming a lawyer, don't" has become a truth for our time, if not yet all time. Nonetheless, many remain committed to the prospect of a career in the law. Geeklawyer continued his outreach efforts to connect with aspiring law students (provided they're young and attractive women, that is); he described their discussion:

All of the above is well and good, but the reality is that the only Chinese companies that sign such agreements are doing so for Wal-Mart or are doing so, knowing full well they will never abide by it. So when confronted by clients who absolutely insist on these "perfect" contracts and refuse to listen to our advise regarding the realities of the Chinese market, we go ahead and write the contract per the clients instructions. We then sit back and wait a few months for them to return to us to write a brand new contract that someone will actually sign. Or sometimes, the client comes back to us and tells us they no longer want to try to do business in China because nobody there is reasonable.

The best contracts are not perfect for any one side; the best contracts are those that provide the most protection possible, while actually working in the real world.

Her large brain and inclination to dispense incisive opinions were not enough to put Geeklawyer off her, even though it is as desirable for a woman to have an opinion as it is for her to have a penis (not at all).Happy New Year to you, Geeklawyer, and to you all!

No, the abiding impression was that for all the uncertainties of the Bar it’s aspirants remain as buoyant and optimistic as ever....

....

Of course she is an impressive high achiever: past president of her University Union, Good degree (albeit only Eng Lit) and winner of GL’s heart. Lofty achievements indeed. But as she is well aware her peers and competitors will also have similarly good CVs despite which she remains undaunted.

Ms LP was equally undaunted even by the realities of new entrants to the Bar: last minute instructions for a hearing 100 miles away requiring overnighter preparation and for a fee that barely buys a starBucks.

Geeklawyer pointed out there were two fast routes to poverty at the Bar: Government funded family law and crime; Miss LP’s career preferences. Daunted and deterred? Not even a little, both admirable and worrying. Miss LP’s response was that she had heard that these stories and prophecies of the Bar’s doom went back 30 or 40 years. True, but Geeklawyer remains of the view that recent trends are accelerating the decline of the Bar in its traditional form. Miss LP says “Meh, Twas ever thus, tell it to the hand” .

Her final response was: “What I really need, therefore, to sustain me is a rich husband”. And she caressed GL’s hand and fluttered her long dreamy eye lashes. There is ambition and over–ambition: madam is hot, but is she that hot?

Header pictures used in this post were obtained from (top to bottom) Carbolic Smoke Ball Co., SeattlePI.com (ABC News Photo), The Village Voice (Mirko Ilic Illustration), Paris Odds n Ends Thrift Store, and Charon QC.